“I was in a state of panic. Did we at least know how many could enter through this gaping door? We did not. After doing some estimates, I put my feet in that door. I knew what England’s generosity had generated, in a parallel position before citizens of the Commonwealth. A staggering Indianization and Africanization of the city of London and others. The English population had reacted violently.

(...)

So all African soldiers? In ten years of war, with an average of fifty thousand a year; that made half a million. And the families, prolific as they are, how many half millions would that be? (...) It was clear that being excessively generous could end up being very expensive.

(...)

And it was never in my spirit to help formerly Portuguese Africans to remain Portuguese in Portugal. They were Portuguese as a result of a legal fiction in the 1933 Constitution. A Salazaran delirium that saw Portugal and its colonies as a single empire, equal from the Minho River to Timor. It wasn’t my fault some people took this fantasy seriously. Salazar himself admitted, often, that Africans did not belong to the Portuguese nation. So how could they be entitled to Portuguese nationality if they don’t belong to the Nation?

(...)

We had to safeguard the Portuguese nationality of those who, having been born in the overseas territories, had consanguinity ties to Portuguese citizens born in European Portugal.”

Source: "Quase memórias do colonialismo e da descolonização [Almost memories of colonialism and decolonialization]", 1.º Volume, António de Almeida Santos

Esta é uma reportagem dividida

em quatro capítulos.

Se ainda não o fizeste,

começa por ler os anteriores.

This is a report divided

into four chapters.

If you haven’t already,

start from the beginning.

“Portugal is my home”

On the porch of the house from where she’s watched life pass by, Helena takes three steps forward and stops, gazing expectantly. The question, “Paulo died?” hangs heavy in the air. Unsteady on her feet, she asks us to come back later—she has been waiting for her heart medication prescription for days and her years weigh heavier in the morning. “I only see him, I only speak to him, on my son’s phone now. When I was younger, I thought life would be easier, but I’ve never got a break. I still sell doughnuts, cakes, fish sandwiches, to make money… I only ask God to help Paulo get his pension”, she tells us.

Paulo Rodrigues hasn’t died, but the “throat complaint” he has suffered for years has taken his voice and silenced him forever. Silenced him, and the indignation he’s accumulated over more than forty years. “Portugal is my country”, he repeated while he still could; as his voice grew increasingly hoarse, and slowly faded away.

“I want to go to Portugal firstly to sort out my health; secondly, to get my pension. That’s all that matters to me now. I am sorting out the trip, the documents… I want to go and then return to Guinea Bissau—I have my house here, I want to be close to my family.” This was his plan in October 2017, when he didn’t know yet the tricks that life would play on him. At the time, Paulo slept with his military logbook under his pillow, the only document that proved what he was: a ranked sergeant in the Commandos division of the Portuguese Army.

He married Helena in a civil ceremony so that, if anything happened to him, his wife would be entitled to a pension as the widow of a former combatant. He asked his niece in Lisbon to help him buy a plane ticket. He saved the money he needed to get himself a Bissau-Guinean passport (43,500 CFA francs—around 66 euros, in a country where the minimum wage is 76 euros). And, when he had everything he needed, he went to the Portuguese Embassy in Bissau to apply for a visa.

He waited, and waited, and waited… time passed by and Paulo continued waiting for a response; meanwhile, his health deteriorated.

Paulo Rodrigues was born Portuguese, “I even had one of the old ID cards”. But Law No. 308—A/75 ### ruled that people born in Angola, Guinea Bissau and Mozambique were no longer Portuguese. This included state workers and soldiers in the Armed Forces—unless they were “up to third-degree descendants” of

- Portuguese nationals “born in mainland Portugal and its islands”;

- Nationalized Portuguese citizens;

- Portuguese citizens born abroad to a Portuguese-born or nationalized father or mother;

- Portuguese citizens born in the former State of India who had chosen to retain Portuguese nationality.

The law also became known as the “vile” law, described by its opponents as “wicked”, “evil”, “criminal”. The law ruled that African-born Portuguese citizens would only retain their nationality if they had parents, grandparents or great grandparents of European or Goan descent. António de Almeida Santos, the law’s author and then Interterritorial Coordination Minister, confessed that “for the Portuguese in the overseas territories who had fought as part of the Portuguese Armed Forces it was a particularly sensitive issue”, because “belonging to those forces was, and is, reserved exclusively for Portuguese nationals”.

Source:

“Quase memórias do colonialismo e da descolonização [Almost memories of colonialism and decolonialization]”,

1.º Volume, António de Almeida Santos

“It increased the risk that those who had fought on our side against their African brothers would be ostracized, punished and even killed, even if their participation had been forced. Which seems to have happened in Guinea Bissau, at the hands of the new authorities. The question was: could we be indifferent to this risk?” This historic Socialist Party figure, who served as minister four times between 1974 and 1983, said he entered a state of “panic” and explains, in his memoirs, what motivated this clean break:

Almeida Santos was proud to have “saved the country from a ‘catastrophe’” and never showed remorse or solidarity for the successive humiliations the “most patriotic of laws” forced thousands of Africans to endure. This was the first step to effectively preclude an African soldier from claiming Portuguese nationality and, as a consequence, the retirement, death in action and disability pensions that the State had promised.

If it wasn’t for this law, Paulo Rodrigues, for example, would have avoided queues that circle the block in Avenida Cidade de Lisboa, in Bissau, where every day dozens of people put their name on a sheet of A4 paper and wait for hours, under a scorching sun, for their turn to enter the Portuguese Embassy. Perhaps, when Paulo arrived in Portugal, it wouldn’t be too late.

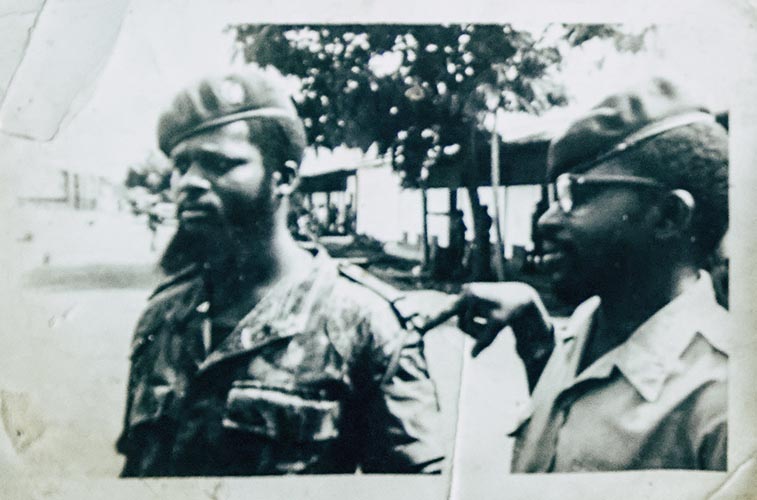

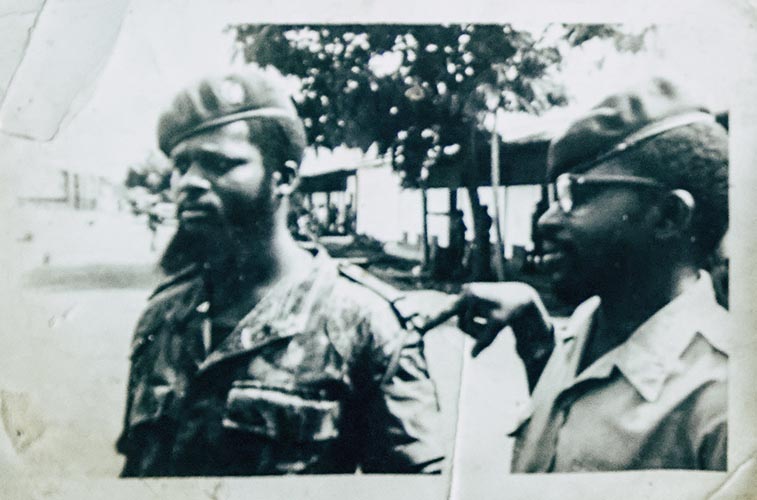

Raul Folques

Commander of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Companies of the Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos

“I think that African soldiers are completely within their rights. They really believed they were Portuguese. Everyone who fought with us in our ranks should have Portuguese nationality. They are Portuguese like me: they were born in national territory, they grew up in national territory… Their nationality was torn away from them after independence. That was abusive, haughty, and frankly it was a very distasteful thing to do.”

Galé Jaló

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 3rd Company

“At the time we thought the PAIGC was wrong. In the end we saw how the Portuguese left, leaving us with our people. If they were right, they wouldn’t have left; they’d be here, right? Guinea-Bissau was a Portuguese colony for how long? Fifty-odd years. Going to the Portuguese Embassy in Guinea-Bissau does no good. I went there before, to register my children, they said they didn’t have time.”

“They don’t want to give him Portuguese nationality because he has no form of income in Portugal. He was injured three times in combat, he’s very old, he has cancer, this isn’t right. We are trying to get him citizenship and to be seen by a medical committee to get him a pension. Let’s see if we can arrange any sort of support, so the man can live here. But I don’t know if we will, it’s complicated”, colonel Raul Folques complained. He was Paulo’s commander in the Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company, between 1970 and 1974.

But what exactly does an African soldier, who fought in the Portuguese Army until 1974, need for his military career to be recognized? To be entitled to what the Portuguese State promised him?

Seemingly simple questions. However, a year and dozens of emails later, the Ministry of Defence still hasn’t responded.

An FAQ on the Ministry’s citizen platform reads: “Can former combatants from African Countries with Portuguese as an Official Language request proof of time served in the military for retirement or benefit purposes?”. The response is, “yes, as long as they are signed up to the state pension fund or receive a state pension”.

Can former combatants from African Countries with Portuguese as an Official Language request proof of time served in the military for retirement or benefit purposes?

(...) Law 9/2002, 11 February, considers the following, among others, to be former combatants: former soldiers mobilized between 1961 and 1975 in the territories of Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique (Article 1, no 2, Section a).

(...)

Finally former soldiers recruited locally are considered former combatants and are covered by same conditions above.

In the terms of that set out in article 3 of Law 9/2002, the group of former soldiers referred to above are only covered if they signed up to the state pension fund or receive a state pension.

So, former combatants as defined above, independently of where they were recruited (mainland Portugal or the overseas territories) and their nationality, who do not fulfil all these requirements, are not covered by Law 9/2002. This means that all former combatants of the Portuguese Armed Forces, whether Portuguese nationals or of African Countries with Portuguese as an Official Language, are treated equally under this law.

(...)

Source: Balcão Único da Defesa

The Army Archives responded to requests for clarification with “Africans from former colonies are not entitled to pensions because they never made Social Security payments”.

But this is incorrect. All the African commandos who fought in the Portuguese Armed Forces between 1971 and 1974 were part of the Army and, therefore, had to contribute to the National Pension Fund. Various documents in the Historical Military Archive prove this.

01/1974

02/1974

03/1974

04/1974

05/1974

06/1974

07/1974

08/1974

09/1974

10/1974

11/1974

12/1974

01/1973

02/1973

03/1973

04/1973

05/1973

06/1973

07/1973

08/1973

09/1973

10/1973

11/1973

12/1973

01/1972

02/1972

03/1972

04/1972

05/1972

06/1972

07/1972

08/1972

09/1972

10/1972

11/1972

12/1972

01/1971

CGA

02/1971

CGA

03/1971

CGA

04/1971

CGA

05/1971

CGA

06/1971

CGA

07/1971

CGA

08/1971

CGA

09/1971

CGA

10/1971

CGA

11/1971

CGA

12/1971

CGA

The problem is that, as they lost their Portuguese nationality in 1975, they aren’t covered by current law. And no one—not even the institutions—seem to know how to help them. The information available on the Ministry of Defence citizen platform is dubious. Calls for information cut out automatically after five minutes. And the questions first sent to the Ministry of Defence in May 2021, and on many occasions since, have still not been answered clearly:

Many African Commandos who start proceedings give up half way, sucked dry by endless bureaucracy. Because they are not familiar with the names of the documents they are asked for; because they don’t have access to the Internet; because there’s no one to explain to them—in an understandable way—what to do.

These barriers are even harder to overcome from a distance, in Guinea-Bissau. The visa to enter Portugal is the big one. The Ministry of Defence online citizen platform states that the Portuguese Embassy in Bissau should respond to military time served requests, but dozens of soldiers who made the request say they never received a reply.

“If I’d had the chance, I’d have gone, but I have no one to help me. If I had my logbook, I could sort the money to get to Portugal. But without the logbook… The embassy doesn’t want to know:

we book an appointment at 5am, we give our name to be seen, but they only see nine people a week. Portugal abandoned us, refused to recognize us, it’s not right”, complained Lamine Camará, soldier, Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 2nd Company, before dying from a stroke.

The Portuguese Ambassador in Guinea-Bissau hides behind the law and takes no responsibility:

“We analyze these cases here; they are still reported today. As regards health care, pensions for family members of those killed in combat, we do everything by the book, as established by law. We cannot do anything not covered by the law or that is illegal, for the simple reason that we obviously exist to comply with the law”, explains José Rui Velez Caroço.

On celebration days, Portuguese representatives in Guinea-Bissau put fresh flowers on the graves where soldiers are officially buried.This happened in May 2021, when Portugal’s President, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, visited the Bissau Municipal Cemetery to pay tribute to the 400 Portuguese soldiers who died in the war and who were never transferred to Portugal. The 249 Africans who also lost their lives serving the Army between 1964 and 1974 in Guinea didn’t get a mention. http://link

Months before, around 25 April, the President gave a conciliatory speech in memory of “those missing from the photo”, such as “the forgotten Africans”, but he never agreed to speak with DIVERGENTE on the matter. ###

Paulo Rodrigues landed in Lisbon two years after requesting his visa. He only made it because colonel Raul Folques intervened with the military attaché, colonel Nuno Duarte, at the Portuguese Embassy in Guinea-Bissau. His decade-long dream came true.

With both feet on the ground in Portela (Lisbon airport) he felt closer than ever to regaining his stolen nationality and the retirement and disability pensions promised to him.

“Shoot me if you want, but I’m going in!”

Galé Jaló

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 3rd Company

“When I arrived, they told me to go to Former Combatants to get the military records [issued by the Directorate-General for National Defence Resources]. I filled in so many documents, but never got my pension. I have loads here. I left some in Lisbon, I threw others away. They never gave me a reason, I ran all over until I realized I wouldn’t get anywhere. I gave up and didn’t go back to ask. They made it clear I wasn’t welcome so I came home. If I’d stayed and someone did something to me, it’d remind me of what I went through and I’d argue. I got myself out of Portugal before that happened and came back to live in my hut.”

At the end of the 1970s, when “everything ended” and he got out of prison, Galé Jaló got himself to Portugal. “I went to see if I could get my money. A friend had told me that, if I got there, it was my right. I tried and tried, but I never got anywhere. Now I gave up trying and just trust in God.” Galé says he ran “all over”, sorting out more and more documents, but, with no end in sight, he gave up. He worked up and down the country in civil construction and returned to Quebo 16 years later, still carrying his dream.

Joaquim Boquindi Mané tells a similar story: “I stayed for ten years, I worked nights as security, but I got nowhere.” He did everything to get his pension, until “he got tired” and, in the end, thought: “OK, maybe it’s not to be. I’ll go back. At least, in Guinea, I have good friends I get on with. They’re old, but they’re my friends.” With the years he spent in Portugal, he regained the citizenship stolen from him by the “vile law”.But, as life hedged towards its end, the Portuguese military logbook and passport—documents he had treasured—became mere symbols of a withered hope.

JOAQUIM BOQUINDI MANÉ

Furriel

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“An old colleague sent me money for the trip and I went to Portugal. While I was there I fell ill and was treated at the Egas Moniz Hospital. It is a large, good hospital. I went to get my pension, I filled out all the forms, everything they asked me to do. I told them: ‘We worked for you; how does this go?’ At the time I still had two more years until retirement, so I left. I got sick and left. If I go now, they’ll give me my pension.”

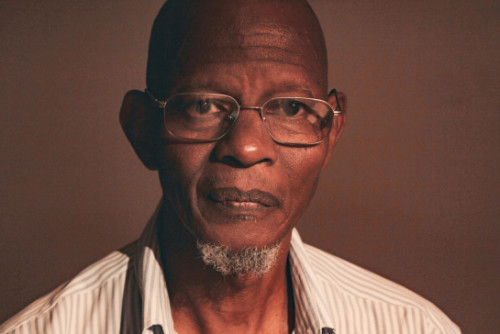

Abdulai Djaló had nothing when he landed in Portela Airport, Lisbon, in April 1983. No family, no work, no money. He went to the Commandos’ Association who helped him and got him a house with other African soldiers, in Lisbon’s Chelas Zone J, a social housing project. “It was crammed, I worked on site and when I got home I didn’t even have a bed—I’d put a chair up against the wall to sleep.” One morning he got up—enough was enough. He went to the Commandos Regiment to ask Raul Folques for help.

“Shoot me if you want, but I’m going in!”, he threatened, desperate. The guards didn’t want to let him in, they didn’t believe him. But he made such a racket they had no choice. “My commander came down from his office and met me at the door. Everyone stared open-mouthed. He put a hand on my shoulder and asked me about the other commandos. Nearly every name he mentioned had been executed. I told him my story; he picked up the phone and got me a job at a chinaware factory in Sacavém [Lisbon] within three days and later as a doorman in the Monsanto campsite [Lisbon].” There Abdulai set up a tent where he lived for 11 years with his wife and children who, in the meantime, he had “sent for” from Guinea-Bissau. “In the Summer, it was boiling”; in the Winter, “a freezer”. He used to be a “war machine”, but today he’s a sweet man. He talks proudly about the house he managed to buy and the education he gave to his children, discouraging weapons and encouraging books. VIDEO

Abdulai Djaló

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“Now I’m good, thank God. I have my house, my family. Your generation talks about university, ours about war. We always live in fear. Even here in Portugal, I know former commandos who won’t have this conversation. I’m here talking because I don’t care anymore.”

Remembering the solitude, the fear and the disdain he was subjected to, Abdulai becomes visibly emotional. “I suffered a lot here in Portugal, I was discriminated against… But, now things are good, this sort of suffering is better than being persecuted and beaten.” He retired in 2013 and today receives a pension for the time he worked in Portugal and the four years he was a commando. He said it was “very difficult” to obtain Portuguese nationality. He is still waiting for a response to the request he made “there” to the Ministry of Defence. “I asked them to reassess my combat injury. The doctor said that I had 60% disability, but when I went before the Military Medical Committee they gave me just 10%.” This difference impacts his monthly pension.

During one operation, a mine left him with a scar he shows at every opportunity, with a mix of pride and resignation. A cursed trophy that left him “with back problems for life”, and that doctors don’t recognize as proof of his disability. “But, look, I can still do squats. For a while my body ached, but I bought a Japanese mattress—those that lie close to the ground—and I got better. It’s really good, it massages and everything, a good investment”. He says this to lighten the mood, while he flexes and stretches his legs repeatedly in a show of agility.

Malam Samá

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“A brother who played in Sporting helped me get the visa and plane ticket to come to Portugal, in 1990. I sorted out my pension while I worked on building sites, the Commandos’ Association helped me sort it all out. I submitted my documents, and they said, ‘You can go where you want, no one is after you here in Portugal.’ Portugal is my homeland because I lived among them where they live; they paid my wages. Here in Guinea-Bissau, I am like a foreigner. I have Portuguese nationality, Portuguese passport; people here call us “Portuguese”, they don’t see us as the country’s children.”

Even today, no State representative has fully justified the non-payment of incapacity, disability and retirement pensions that Portugal promised in signing the Algiers Accord ###.

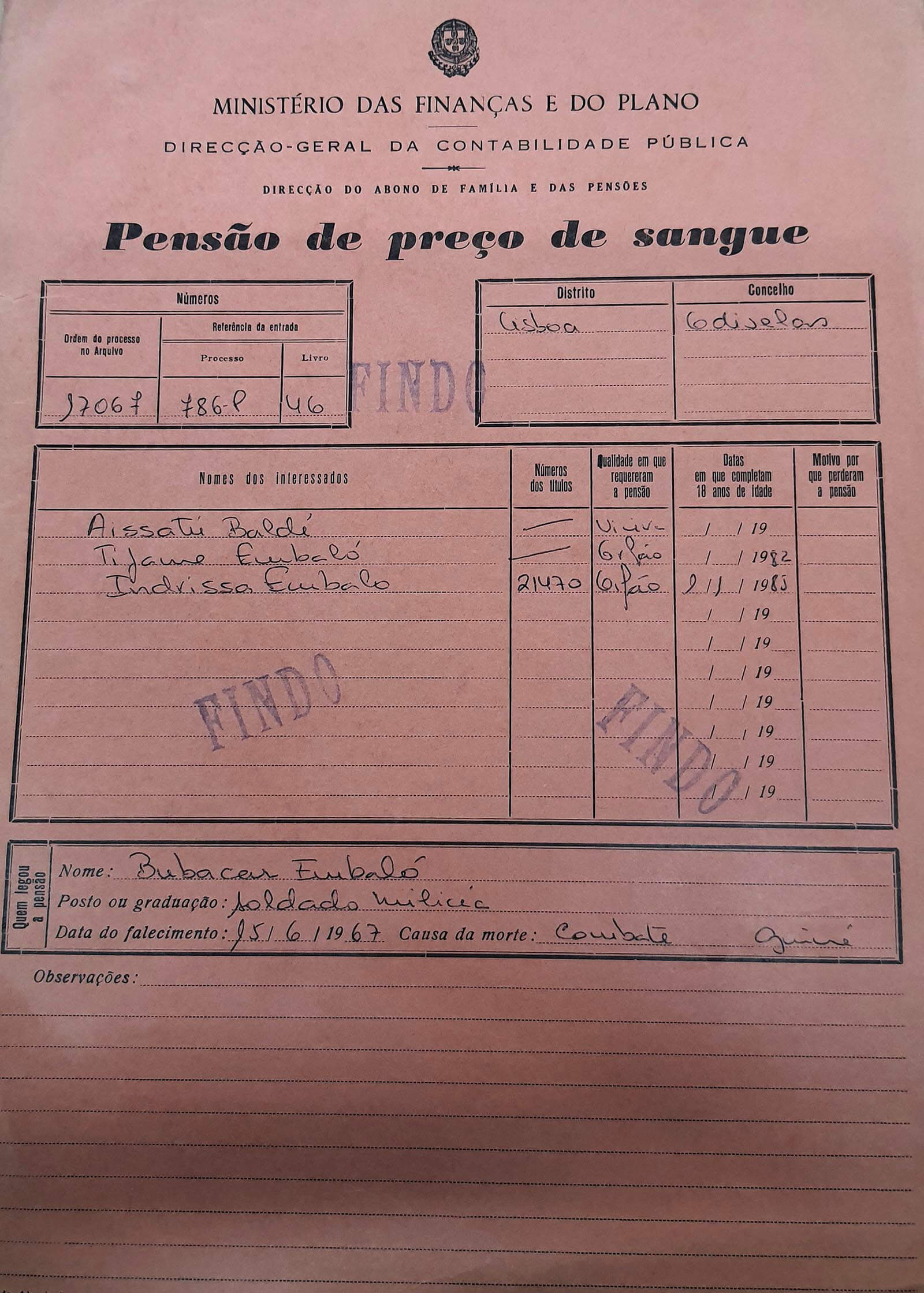

“Documents were found in the Ministry of Finance Secretariat Archive and Digital Library that prove that the Portuguese State pays death in action pensions to former combatants from the former colonies, both from the Republic of Mozambique (1979) and the Republic of Guinea-Bissau (1981 and 1982)”, Margarida Peixoto, press advisor for the Ministry of State and Finances confirmed. In the case of Guinea-Bissau, after 1975, documents show five cases that were rejected ### and one accepted.

In 1983, after a long negotiation ### and without the consultation of Guinean soldiers, Council of Ministers Resolution No. 18/1983 ### resolved that the payment of these pensions would be transferred to the Bissau-Guinean State. In exchange, Portugal would pardon Guinea Bissau’s debt of 200 million escudos [998 thousand euros].

“The Council of Ministers, meeting on 6 January 1983, resolved to (...) authorize that Guinea-Bissau's claim on the Portuguese State— resulting from the payment of disability and death in action, survivor and retirement pensions owed by the Portuguese State, respectively, to Guinea-Bissau citizens who served in the Portuguese Armed Forces and to Portuguese state workers residing in Guinea-Bissau—be used to pay, by way of compensation, the following debts owed by the Republic of Guinea-Bissau to Portugal."

Source: Council of Ministers Resolution No. 18/1983

Portugal therefore transferred the responsibility of pension payments to soldiers recruited to the Armed Forces in Guinea to the same political forces against whom these soldiers fought during the war—the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), which was in power at the time. Even so, and despite this agreement, the Portuguese state continued to grant pensions to African soldiers who managed to regain their nationality and provide evidence for their involvement in the army. Abdulai Djaló and Malam Samá are two such cases.

On the one hand, Portugal transfers the debt it has with its soldiers and “former citizens” to Guinea-Bissau; on the other, it ignores this agreement and grants pensions to those who, having arrived in Lisbon, manage to navigate the process.

A legal limbo that lawyers and political representatives seem unable to explain.

Public Administration bodies never responded to these questions and, nearly 50 years later, the Portuguese State and Government continue to shy away from their responsibilities.

In July 2020, the Portuguese Parliament approved changes to the Former Combatant Statute ### that claims to want “to obtain justice” for those who participated in the Colonial War and underlines “a dignified place for those who fought for Portugal throughout history”. The document covers “only and exclusively those who made social security payments in Portugal and who are, as a result, pensioners of the Portuguese State”. In theory, all Africans who fought in the Army, who were Portuguese citizens and made social security payments until 1974, are therefore covered by this Statute. In practice only those who have the money to pay for a passport, buy a plane ticket to Lisbon and cover the costs of living in Portugal, could dream of starting the process to request what was promised to them nearly 50 years ago.

Galé and Joaquim gave up along the way. Abdulai and Malam spent years sending papers to and fro until finally they proved they had been commandos in the Portuguese Army. They call themselves the “lucky ones”. Abdulai laments the situation, “It is difficult for anyone who remained in Guinea-Bissau to gain nationality and a pension. I feel sorry for the commandos who stayed. They took up arms with me, we went out into the bush together, we fought, and they get nothing! With nothing to eat. A colleague of mine called me the other day to ask for 10 euros to buy sugar… 10 euros! I am so, so sorry but I can’t do anything. Every month, the Portuguese government could give them 20 euros, or not even that, to buy rice so they can eat; send a doctor to treat them once a year. That isn’t much for the Portuguese government”.

We are a digital publication, but our team works in analogue. We write for people, not algorithms. If you want to suggest a topic, or ask us about our work, send us an email at: info@divergente.pt

Owner: Bagabaga Studios, CRL VAT: 510672531 ERC number: 126622 Periodicidade: anual Director: Diogo Cardoso Editor-in-chief: Sofia da Palma Rodrigues Adress: Rua de Arroios, 25 C, 1150 – 053 Lisboa Portugal

Follow us on social media to find out about our events and follow what is happening at the DIVERGENTE newsroom. We post news there.

“He died swollen like a pig trying to reach Portugal”

Julião Correia is one of those who had no choice but to stay in Guinea. “Lots of friends, brothers, died, without making it to Portugal. They hoped to receive their money, but they couldn’t go. We are just left here. I hope I’ll get my pension, but when? I’m 77 already, I’ll be 78 soon. When will I get the money to go there? When? Who’ll take me?

I still feel Portuguese, I have a Portuguese commando document, but the Portuguese don’t recognize the troops they had in Guinea. I’ll always be Portuguese because I swore an oath to my country.”

Lamine Camará shares the same indignation. “Honestly, why didn’t I join the fight for independence? I turned against my parents, against my siblings… Portugal should recognize their former partners who served them. Because we violated the principle of our own land, we took the colonizers’ side. I feel Portuguese because I am Portuguese. If I fought against the PAIGC flag, I belong to the other side.”

I am Guinean, I really am, but if they ask me I will say I belong to Portugal. Because I swore on the Portuguese flag. Any trouble I have today is because of the Portuguese, not the PAIGC. It’s sad, a man fights for a cause but is then pushed aside. In other parts of the world… you see how former combatants who fought for the French are treated…”, he complains. He is talking about the Harkis, Algerian soldiers who fought on France’s side in the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62). Emmanuel Macron apologized to these troops in September 2021.

Julião Correia and Lamine Camará died just months after this sort of catharsis. Many Guinean African Commandos spoke for the first time about the war and the hurt they felt for Portugal only as their lives hurtled towards their end; a purge, finally releasing something that had gnawed at their insides for so long. VIDEO

The African Portuguese Army soldiers’ demands are not a thing of the past. Former combatants, children and widows, still attend demonstrations every year outside the Portuguese Embassy in Bissau. “We protest but the Embassy Colonel [Nuno Duarte, military attaché to the Bissau-Guinean Portuguese Embassy] never responds. I refused to accept this and petitioned the Portuguese Ministry of Defence and the Presidency of the Republic directly”, Amadu Djau says. Confident about the legitimacy of his demands, the president of the Association for Former Combatants of the Portuguese Armed Forces in Guinea Bissau led, in September 2022, a public petition addressed to the Portuguese President, calling for Guinean army veterans to be considered Portuguese again.

Fernando Cabral

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“Why would I not feel Portuguese? They ruled at the time. If the Portuguese wanted to look after the Commandos, they wouldn’t have abandoned them. I don’t talk with any of them in Portugal. Abdulai came here one year, we had a great time. We were friends, we got on. How long ago did the ‘tuga’ [a term for a Portuguese person that can be derogatory] leave? They said we were entitled to a pension… Still waiting. Not even 25 francs. They’re waiting for us to die. And when we die, you get it all.”

Braima Bari

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 3rd Company

“I thought that Portugal would do something for the Commandos, but no. Portugal should’ve helped us. There are so few of us left: most are dead, some got to Portugal. We were abandoned.”

Mário Sani’s body is not strong enough for this fight. He is so weak that it takes all his might to put one foot in front of the other and walk half a dozen metres. He talks of how, one day, his blood pressure plummeted and he decided to go to Bissau, to ask the Portuguese Embassy for help:

“I saw a man there and asked him to help, but he said he couldn’t. I saw he busy and left. Some of my colleagues went to Portugal and got a pension, but I couldn’t because I’m sick and I have no one to help me, no one. I’m alone here. I’m just waiting to die now.”

At one time, Mário still hoped that the country he gave his youth to would come to his aid. But, two years before dying “swollen like a pig trying to reach Portugal”, the thought didn’t even cross his mind. Mama Sani describes his brother’s last days, “When his body swelled up like that, I sent a photo to Jaime—another brother in Lisbon—to try to get him out of here. But he died within the week. He was the youngest of all three.”

Before dying, Mário asked to be buried in his backyard, next to his dad and his son. Just metres from the porch where he told his story for the first time. Hoping for, perhaps, in death, an end to the solitude that characterized his life.

Joaquim Boquindi Mané left Portugal before getting his pension, because he was sick. With a “home remedy” he improved, but not for long. Jara Sané watched her husband die in her arms on Monday, 16 March 2020 at 10am. Her dream of officially marrying and getting the family Portuguese nationality would never come true. “He was sorting out the documents to get married, but he died a few days later.”

Helena will never hear Paulo’s voice again, but this doesn’t stop him from calling her every week. “He writes messages on a piece of paper and then asks someone to read them. He asks me how I am, how are the children, if we have food to eat…I tell him not to worry, to sort out his health, that I’m fine, to not worry.”

When Paulo went to war, Helena stayed home looking after the house and children. Fifty years later, history repeats itself. “How do I feel? All I do is worry. Have you seen me? I used to be strong, but now just worries. I worry about how he is there, in a foreign land. When you are at home you do what you want, but in someone else’s…”

Despite everything, Helena and Jara’s hope seems unbreakable. Helena believes that if Paulo gets his pension, they will be able “to sort out the house and rest”; that, with this money, her husband will be able to go to Portugal when necessary to get the treatment he needs. Jara isn’t giving up either. “I need help sorting out the documents for me and my kids, then I will sort out the pension. Maybe the embassy will help us.”

It was Sunday morning on 20 October 2019 when the phone rang. “Hi, it’s Paulo, I’m in Lisbon, I’m in Portugal!” The next day, Paulo, his cousin Romão and two other colleagues from the Commandos—João Nandingna and Jorge Sanhá—followed in a car from the Queluz train station to the Commandos Army Regiment in Carregueira Sierra, Sintra.

Once inside, Paulo holds his head up high, stands as straight as he can and gives a deferential greeting to each soldier he sees. “Only two people go in with him. Not the whole regiment, the doctor doesn’t need to see everyone”, an official tells them.

“Do you have Portuguese ID?”, the “Doctor” asks. No. “So you don’t have any Portuguese ID number, citizen card?”, she insists. No, the military logbook is the only proof of the story he’s come to tell. That and the many evils his body bears. “What’s wrong with your voice?”, she asks. He doesn’t know. He’s spent the last two years trying to find out.

— He needs to start the process. He’s come from Guinea; he doesn’t have anything set up. He’s a ranked second lieutenant, he suffered various injuries during combat, as you can see in the logbook. We need a report for him to be considered a disabled member of the Armed Forces”, his friend João Nandingna explains.

— But, look, I as a doctor, the most I can do is look at his injuries and document them. To get this, you need to state that these injuries were a result of the war and I can’t rule on the cause, because I don’t know how these injuries came about: war or otherwise. I want to believe you, but I can only look at the injuries and describe them. The procedure you are seeking requires another level...

1461 days and 4139 kilometres later, Paulo was still trying to reach this other level. In 2020 he requested a Medical Committee at the Lisbon Armed Forces Hospital, but he never received a response. “The letter with the appointment must have got lost”, replied the hospital when lawyer Fernando Ramos asked about the status of the request.

The lawyer says he has been “unofficially” informed that the Army Chief of Staff, admiral António Silva Ribeiro, wants to recognize all Guinean African Commandos as Portuguese, but that “it will only be possible with political support”. Lieutenant-colonel Alexandre Varino, spokesperson and public relations officer for the General Staff of the Armed Forces, denies this. “His Admiral Chief of Staff has never made a statement on the matter, because the Armed Forces Chief of Staff does not have the legally-assigned power to offer Portuguese nationality to the Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, who fought in the Army between 1971 and 1974. It is the responsibility of the member of the government responsible for justice”, he says in an email.

After a throat cancer operation that left him mute, Paulo lives off the kindness of some Maria Teresa de Calcutta Missionary nuns in Chelas, Lisbon. He waits there to see if life will turn a corner and if the Portuguese State will take responsibility for the war injuries it forced him to suffer. Only after this, “if it’s God’s will”, will he be able to go back home where Helena awaits.

The story of 25 April 1974 is of a bloodless revolution with carnations instead of weapons. Where a group of white soldiers won freedom through a peaceful revolution. At the same speed with which this version of History was repeated, another was silenced: that the freedom won by the April captains was won also because these men fought in Africa side by side with black soldiers.

The end of the dictatorship brought an abrupt end to Portugal and the multiracial nation it had defended until then. It tried to wipe clean the legacy that decades of colonial occupation in Africa had left on its national identity, and it banned the right to citizenship of black men and women who had previously formed part of the empire.

In November 2022, as we publish the last chapter of this report, at least six of the twenty commandos we have spoken are dead. In Guinea Bissau, Angola and Mozambique, there are thousands of men waiting for Portugal to recognize their participation in the Army.

We are a digital publication, but our team works in analogue. We write for people, not algorithms. If you want to suggest a topic, or ask us about our work, send us an email at: info@divergente.pt

Owner: Bagabaga Studios, CRL VAT: 510672531 ERC number: 126622 Periodicidade: anual Director: Diogo Cardoso Editor-in-chief: Sofia da Palma Rodrigues Adress: Rua de Arroios, 25 C, 1150 – 053 Lisboa Portugal

Follow us on social media to find out about our events and follow what is happening at the DIVERGENTE newsroom. We post news there.

Sent

Sent