“[It was necessary] to create soldiers who could fight guerrilla warfare, keep their heads in extreme weather conditions, be clever enough to escape dangerous situations, bold enough to hunt the enemy relentlessly, with the courage to use silent weapons and a team spirit that would ensure they would never compromise the group. A cool head was needed to let the enemy get close, or to close in on the enemy without rushing in, compromising themselves or their group, to be fit enough for the long marches, to have a physical and moral stamina to overcome the toughest of tests, without getting disheartened or despondent. They needed patience to be able to wait, hours if necessary, without talking or moving, to surprise the adversary—the perseverance to hunt the adversary whatever it took. To be able to unleash a brutal blow and quickly disappear, like ghosts, day or night. Most people don’t have the sum of these qualities. That’s why it was necessary to create teams, specially selected and trained for the job, based essentially on a voluntary service.”

Source: “Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África (1961-1974), 14.º Volume: Comandos”, Estado-Maior do Exército

Esta é uma reportagem dividida

em quatro capítulos.

Se ainda não o fizeste,

começa por ler os anteriores.

This is a report divided

into four chapters.

If you haven’t already,

start from the beginning.

“They wanted

to build a company

of commandos

to bring the war

to an end”

Youth is eternal, frozen in time—“my time”. In “my time”, we are nearly always better looking, more tenacious, more fiery, we are nearly never scared, and we rarely think that our moment will pass. In remembering “his time”, Galé Jaló can’t help but talk about the years he spent in the Commandos. His eyes sparkle intensely and his smile, that starts as just a trace, quickly takes over his face: “I’ll never forget, not even now, how to present arms.

The Commandos weren’t just any troop, we were special, the most important men in Portuguese Guinea. We earned more than the common soldiers, we had money and prestige. Women would say: ‘Now here’s a real man’.”

Many men came back from the war in pieces, or never returned at all, but Galé Jaló, soldier of the Portuguese Guinea African Commandos 3rd Company, doesn’t focus on that: “The Commandos training was hard but, after three or four days, we got used to it and stopped being scared. We didn’t want any of the others to say ‘that one’s a coward’. Ah, I was in shape back then, just look at my logbook…” Youth is also about absolutes: you block out what you don’t want to remember and make it impossible for the present and future to equal its splendour.

Galé Jaló was working on the Saltinho Bridge construction, one of the big public works undertaken by the colonial administration in Portuguese Guinea, when a sergeant called him over and said: “You have to give your name to the Commandos or the Marines; if you don’t, you’re off to the Caravela island [one of the Bissagos Islands, where prisoners who defied State orders were held].”

In 1972, when the war was drawing its last breath, Galé went to Bissau to pick up his uniform and went on to the Fá Mandinga barracks, in the east of the country. There, the new recruits, now part of the Portuguese Armed Forces, came together and started their training to join the three companies of the Portuguese Guinea African Commandos Battalion—all of them hand-picked, on governor António de Spínola’s orders.

Source:

“Os comandos da Guiné”, Mama Sume — Revista da Associação de Comandos, n.º 75, Raul Folques

Paulo Rodrigues was another of those men. A captain pulled him from Rifle Company 6, where he was already conscripted, and took him to Fá Mandinga: “They chose Africans from various contingents, they wanted to build a company of commandos to bring the war to an end—this special troop was much better than the normal one, it was everywhere.”

Paulo remembers those times with a contagious joy, he speaks of himself and his brothers in arms as if they were real peacocks: “I was young, funny… At the time, girls would look at me and like what they saw. When we wore the Commando uniform and walked around Bissau, everyone would look at us. We would jump from moving cars and land on our feet.” He spent everything he earned on food and parties: “I wasn’t interested in anything else. I was young, I didn’t think of the future… When we had time off, I never went home, I went out with my cousin on the bike.”

The Portuguese Armed Forces needed strong, fearless men, able to cope with long stretches alone in the bush. Men who the military chiefs could trust blindly.

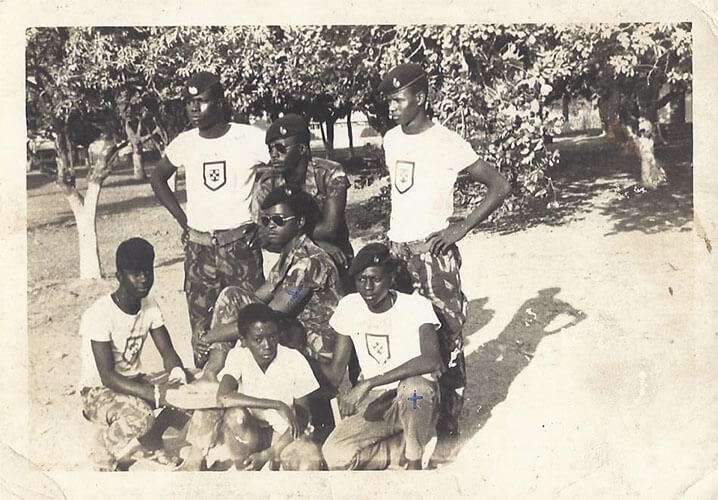

With a better knowledge of the land than the continental troops, the African Commandos were the trick up Spínola’s sleeve that he believed he could use to win the war. It was the only elite troop in the history of the Portuguese army composed exclusively, from top to bottom, of black men. They were the most athletic, the bravest and the boldest of all Portuguese Guinea—at least this is what they still boast today.

Source:

“African Troops in the Portuguese Colonial Army, 1961-1974: Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique”, João Paulo Borges Coelho

The creation of the Commandos

Malam Samá believes, still today, that it was God’s will that he survived the Commandos troop. God and the good luck charm that his father made him to prevent bullets from hitting him in the bush: “It was a rope that tied around my waist and protected me.” When he arrived at the Fá Mandinga barracks, the recruits were divided into groups of 25 men.

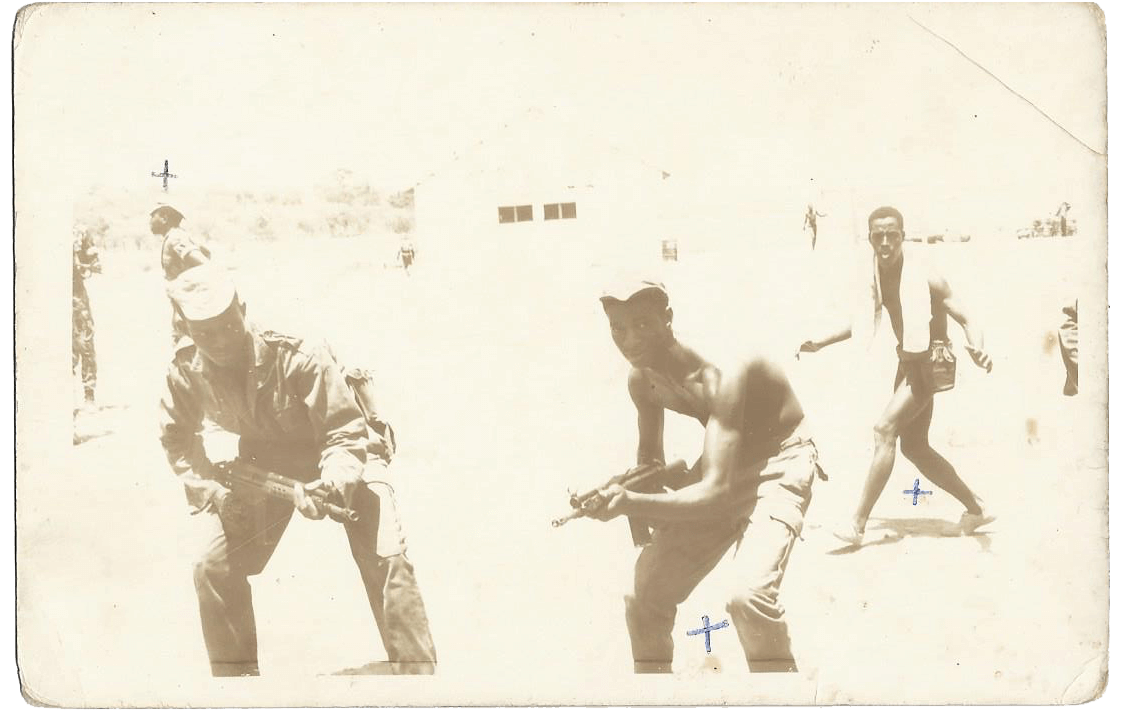

They trained day and night: push-ups, sit-ups, running and shooting. There was little time left even for sleeping:“We spent a year there, just on the Commandos course. The training was hard, people died, but only one from our company did, in the Bafatá river. We went to do the sea training, he got in the river, he didn’t know how to swim. He swallowed water and drowned. Later he turned up and we buried him. Some also got bullet wounds and one had a grenade explode in his hands—they were blown straight off.”

Joaquim Boquindi Mané

Lance-corporal

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“You had to be quick, agile, have a steady hand and a good aim. If I go to shoot wood pigeons now, I’ll shoot and kill two or three. During training, they said that each bullet had a name, we didn’t dare shoot randomly. The training was hard, many died there. We learned to shoot, to drive cars, to jump from helicopters. In the Commandos, there was a little fix they gave us to abate our fear: they would put pills in a 200-litre drum of water and we would drink from there. If we were scared, we’d find courage. Some thought it was a drug and wouldn’t drink it.”

In Fá Mandinga, under a blazing sun, the future Commandos were made to cross rivers with crocodiles and to train with live bullets. There, they manufactured war machines in a kind of human production line: those who couldn’t handle the harshness of the training, like a defective automaton, were cast aside.

Many lost their lives during the training, or were left injured. But power and fame, when they come knocking, seem to make people blind to these misfortunes. While it’s true that, at the beginning, many of these men were made Commandos against their will, it is also true that they quickly got used to the gifts this new place offered: the tight and well-starched camouflage, the shine of the black polish on their leather boots, and the weapon that they got to wield, all this gave them a status that made them proud.

“The first time

I saw a dead person

in the bush, I was

traumatized for

nearly a week”

Julião Correia

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“The war we waged was soldiers against soldiers; we didn’t attack villages. Anyone who went to the bush and didn’t die, when they returned to the barracks, had a little party. The canteen was open: if you wanted a beer you’d drink that; if you wanted wine, you had wine; if you died you lost everything.”

Paulo Rodrigues

2nd Lieutenant

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“In the war, we know we’re going to the bush and things will happen. Even if we were scared, we were still going. There were only two possible outcomes: we would save ourselves, or we would die. When you are young, you are fearless.”

Armando Paulo Sambú

Lance-corporal

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“We would walk two, three, 15 days in the bush, eating combat rations. They would give us sardines and that big bread. We couldn’t be scared, how would we cope? We didn’t kill anyone directly, but we’d exchange fire. They shot, we shot, no one knew exactly where the bullets would fall.”

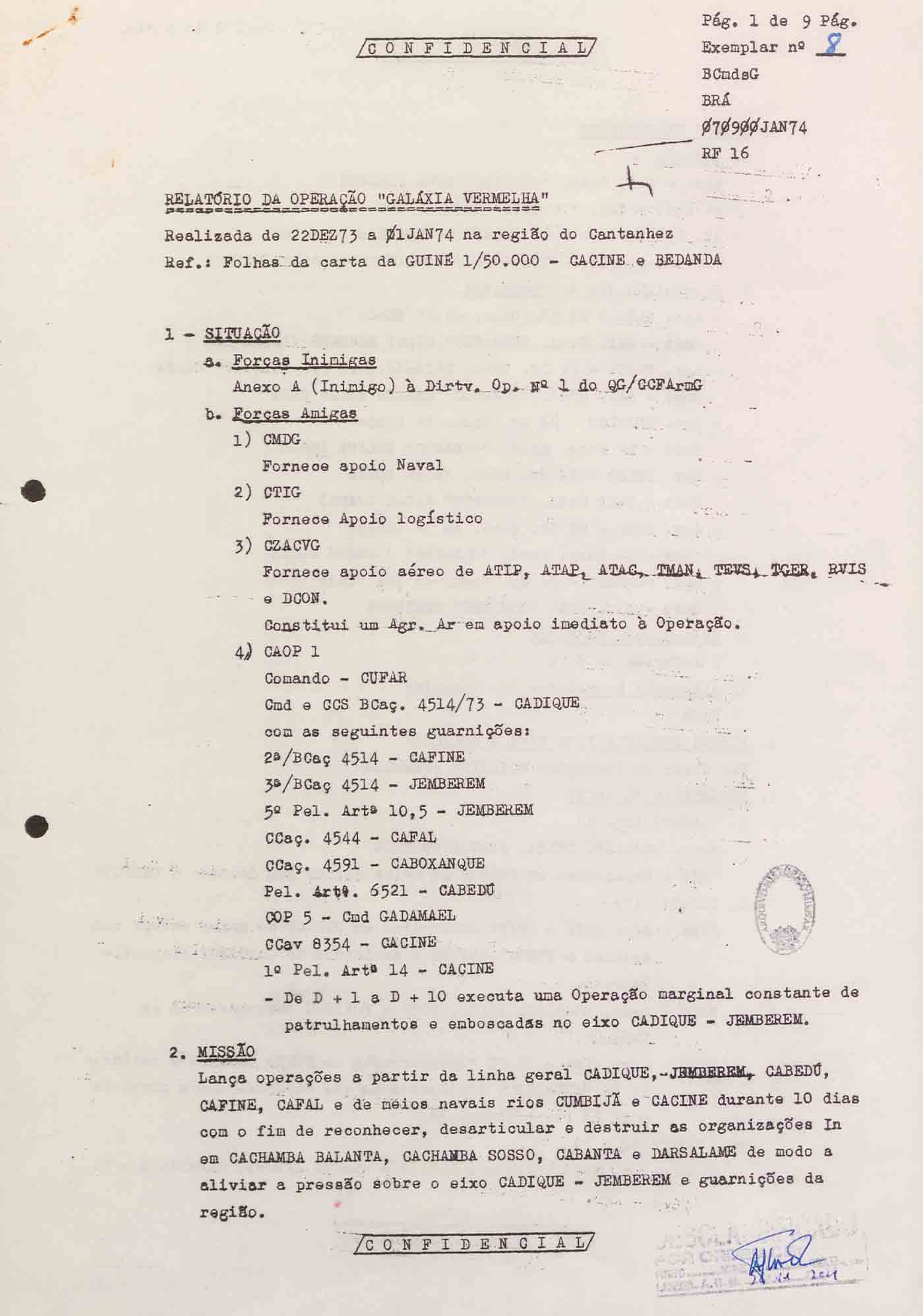

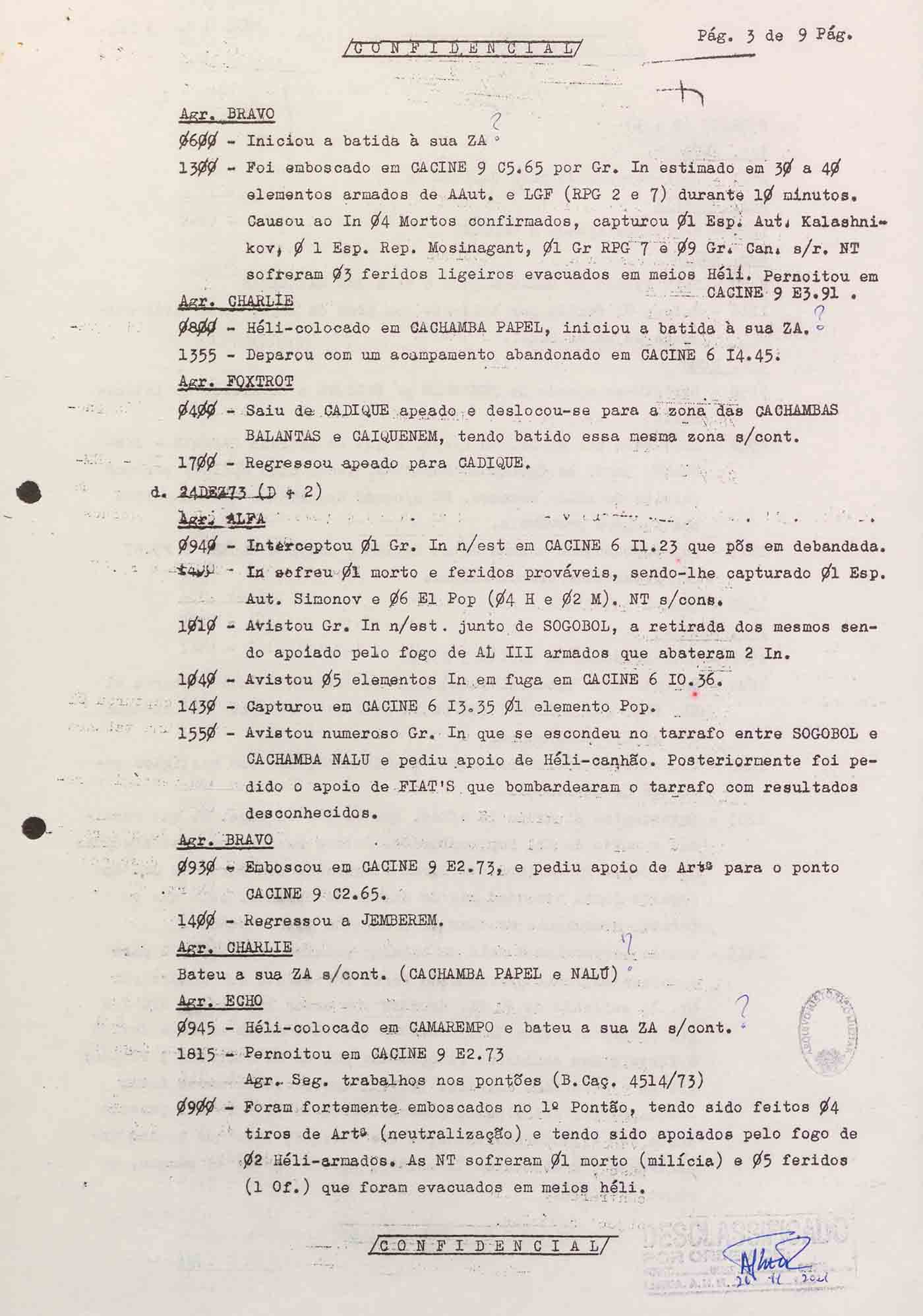

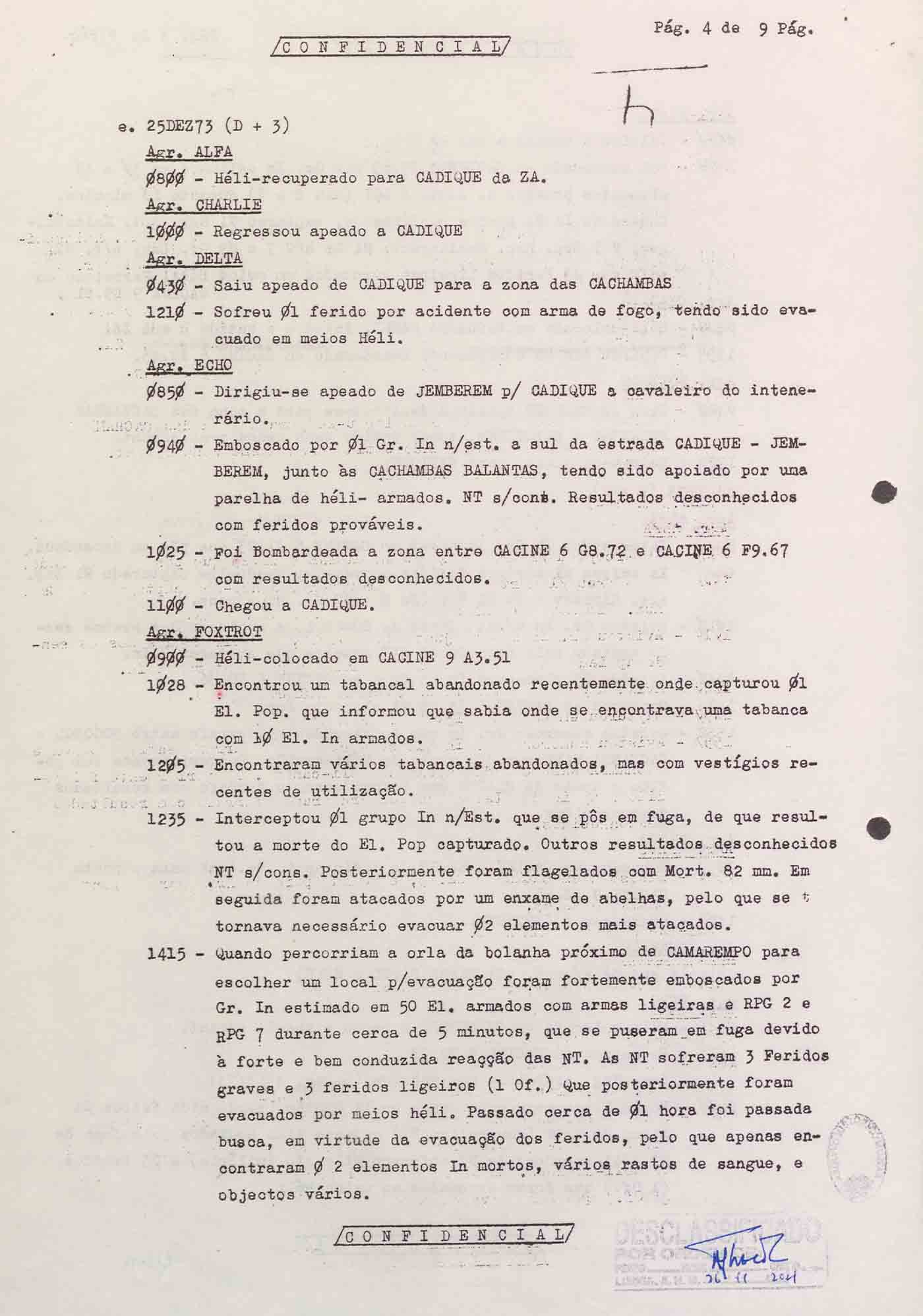

After recruitment, the African Commandos were then sent to Bissau. They had to go to the Brá barracks twice a day and would only be part of the action on the special operations days. They were the Portuguese army’s “secret weapon”, put into action for the most difficult, risky missions. The objective was, typically, to reach the most isolated areas of Portuguese Guinea, where the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) guerrillas were camped. The specific destination was nearly always unknown. Keeping this secret was the only way to guarantee there would be no information leaks between relations and friends on opposite sides of the struggle.

They dressed in camouflage and were dropped off by helicopter, at times “over five metres off the ground, with no parachutes, nothing,” recounts Galé Jaló. They would carry a machine gun, grenades, a bush knife, a munitions belt, canteen, sleeping bag, waterproofs and combat rations. The objective was nearly always the same: capture elements of the PAIGC and destroy the movement’s bases.

The Commandos were the first into danger, they were at the forefront of operations and protected the white troops, who would come in behind. At the end of each operation, their aim was to disappear without a trace.

Source:

“Resenha Histórico-Militar das Campanhas de África (1961-1974), 14.º Volume: Comandos”, Estado-Maior do Exército

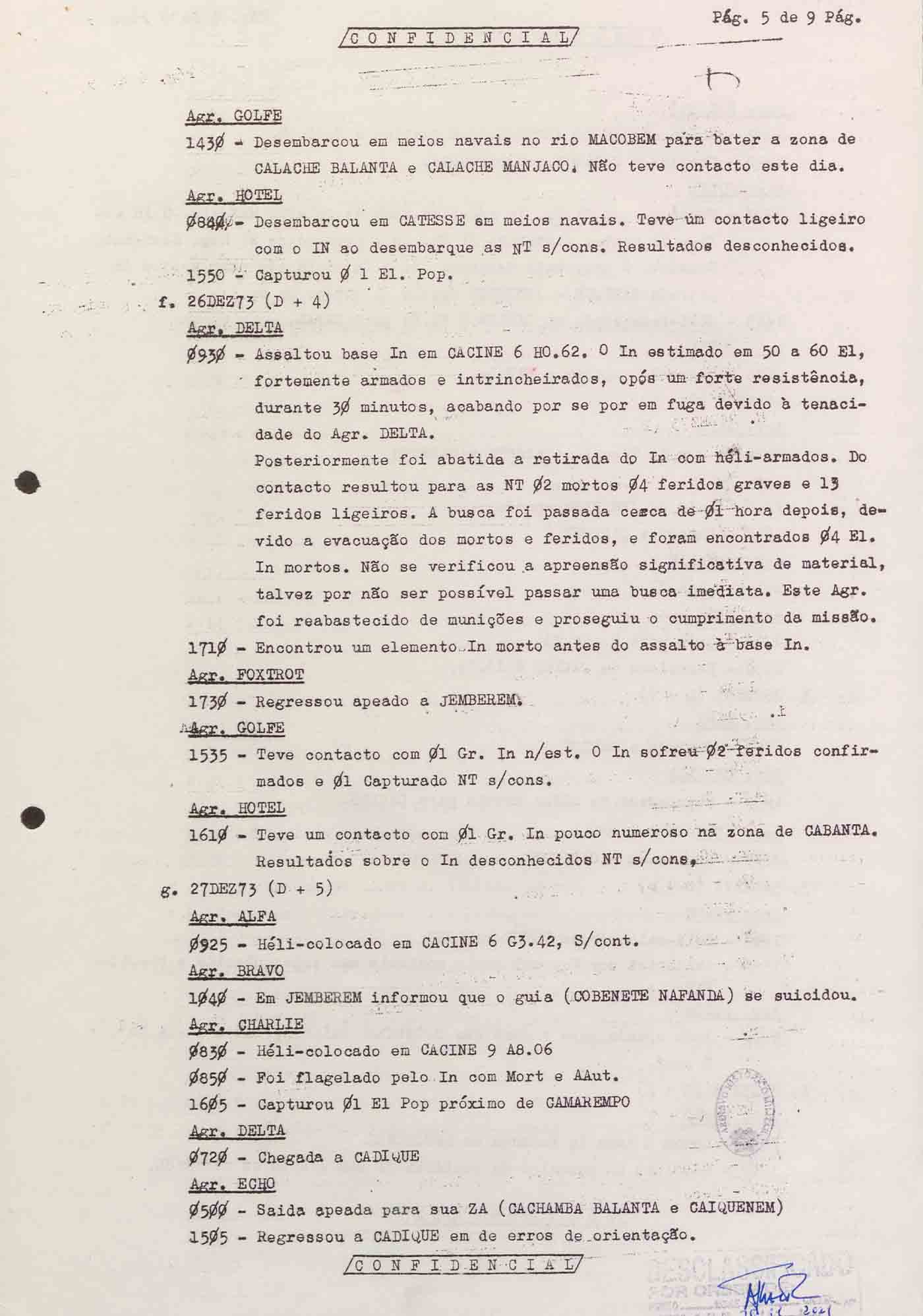

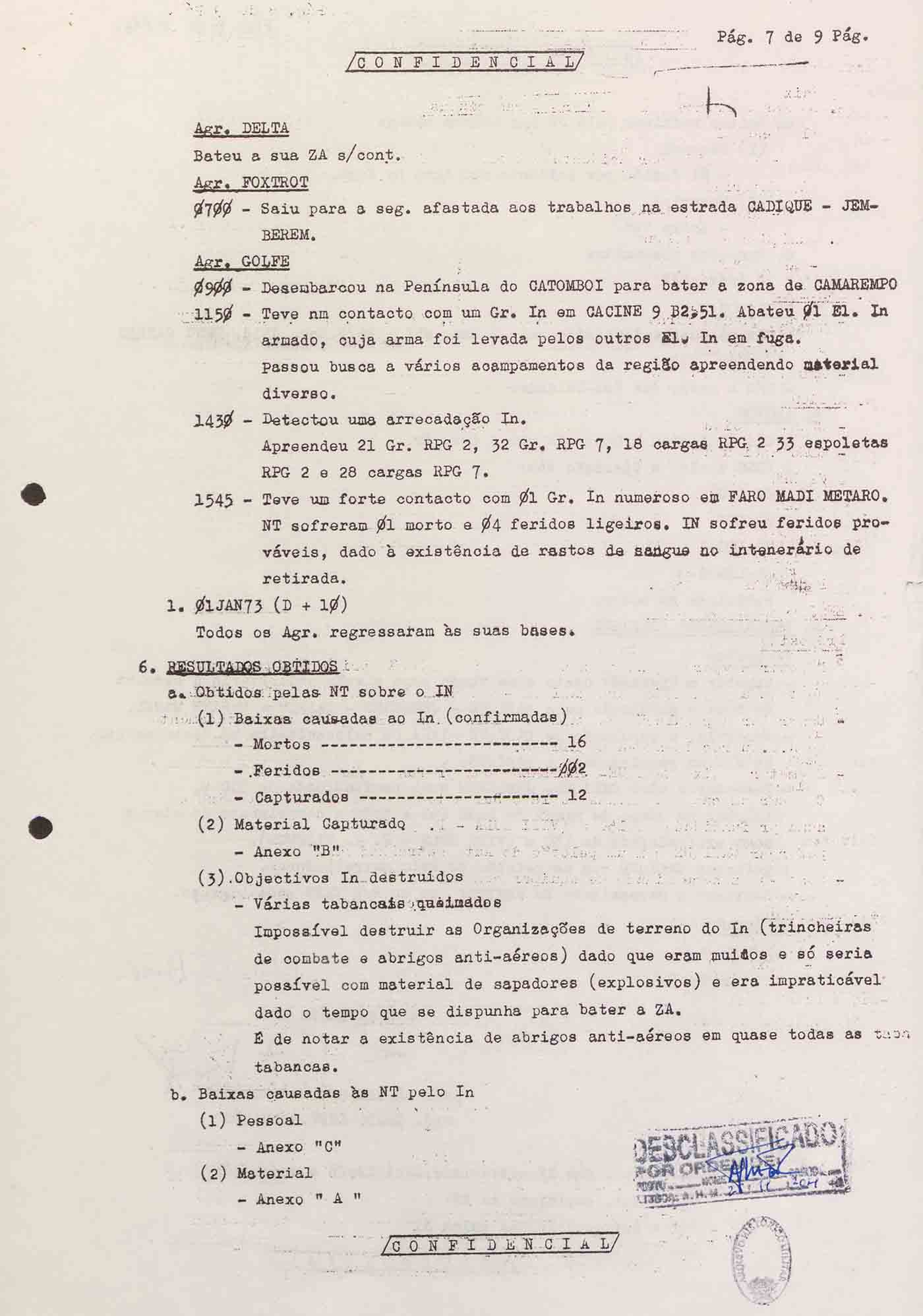

The legend Marcelino da Mata

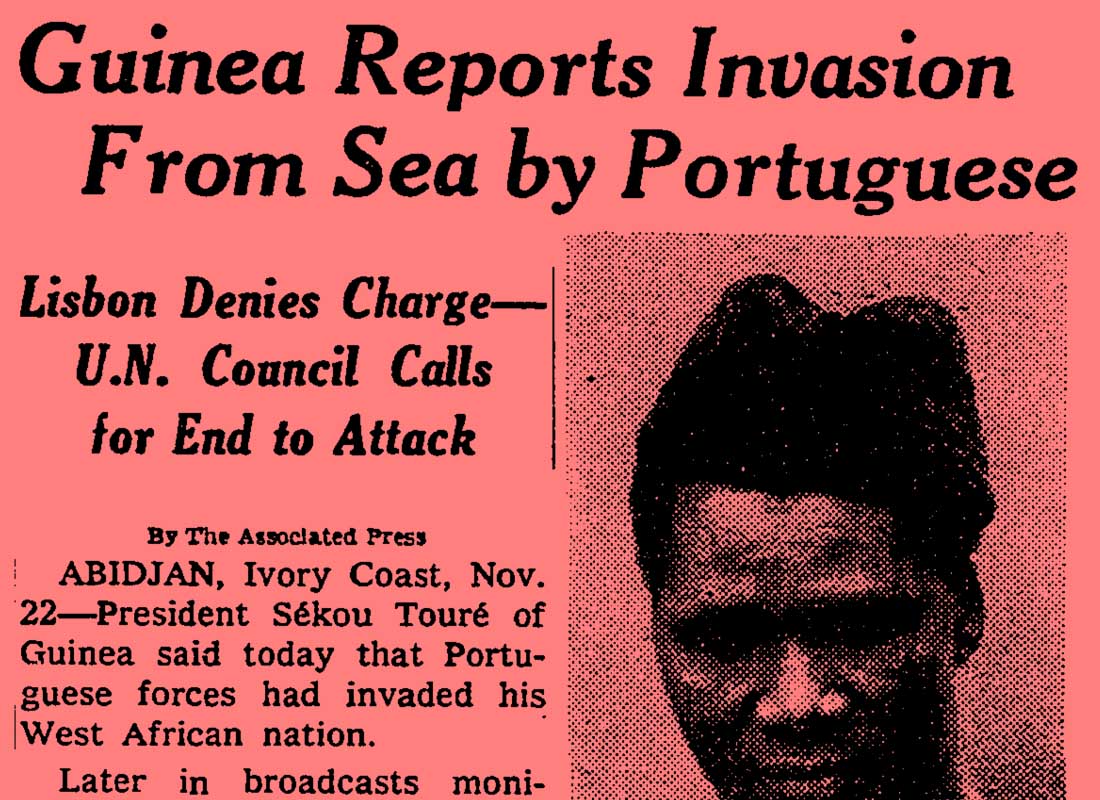

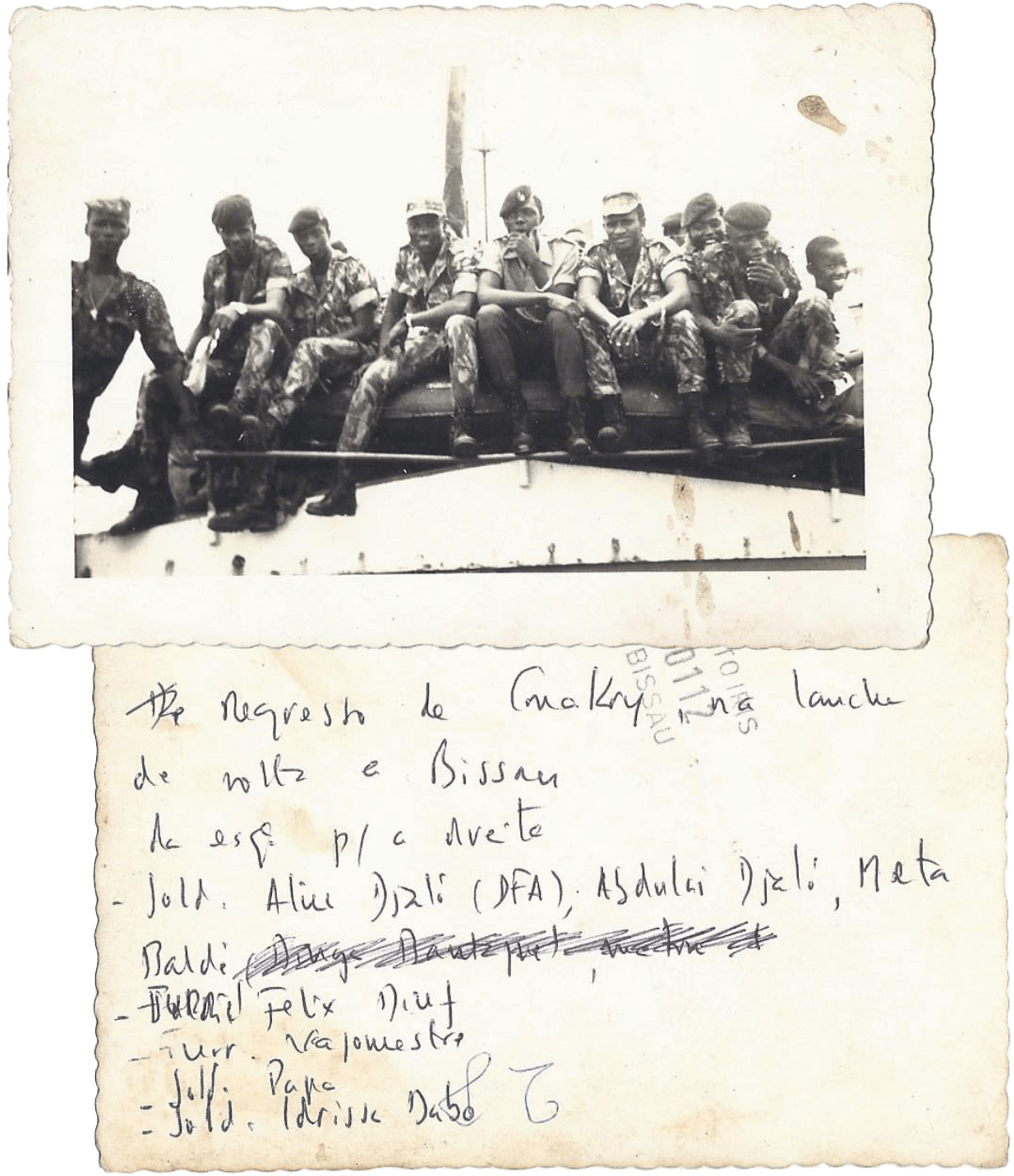

Of the more than 17 operations they participated in, the Mar Verde [Green Sea] was one of the most significant. Aiming to undermine the support given to the PAIGC from neighbouring Guinea, which had already gained independence from the French, in December 1970, Spínola planned a coup d’état and ordered Portuguese military to wear the Guinea-Conakry army uniform with a triple purpose: to topple the head of State Sékou Touré from power, to capture Amílcar Cabral and to free the Portuguese who had been imprisoned there by the PAIGC.

Source:

“Guerra Colonial”, Aniceto Afonso e Carlos de Matos Gomes

To carry out these missions, he called on recruits from the African Commandos 1st Company, which was starting to train at this time. He took them to the island of Soga, in the Bissagos archipelago. Everyone repeats the same story of what happened: they were informed of the objectives and what each of them must do upon arrival at Conakry.

Mamadu Camará

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“They wouldn’t let us go with anything that could be linked to Portugal – uniform, arms, food; everything came from abroad, even the cigarettes. I felt like I wouldn’t be coming back, just like the others who left and never returned. I was scared that a submarine would intercept us on the way and put an end to us before we even arrived in Conakry. But we got to the port, we got off, completed our mission and came back.”

Luís Sambu

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“The operation that I remember most vividly is the Conakry mission. Spínola saw that we were in a bit of a tight spot, he took us where we didn’t want to go and that game nearly got a lot of us killed. The objective was to free the Portuguese. When they saw us, they didn’t believe that we were commandos, because we were dressed in the other side’s uniform. But God helped: we got them out, they got the boat, they got to Bissau and went back to Lisbon. We were the last to return.”

A “suicide mission” which João Bacar Djaló, captain for the 1st Company of African Commandos, opposed. Mamadu Camará, one of the Company’s soldiers, tells of how the captain told the commander-in-chief that he wouldn’t send his boys to death. But they weren’t given the option: either they went, or all the troops would be left on a bomb-rigged boat in the middle of the sea.

An attempted coup

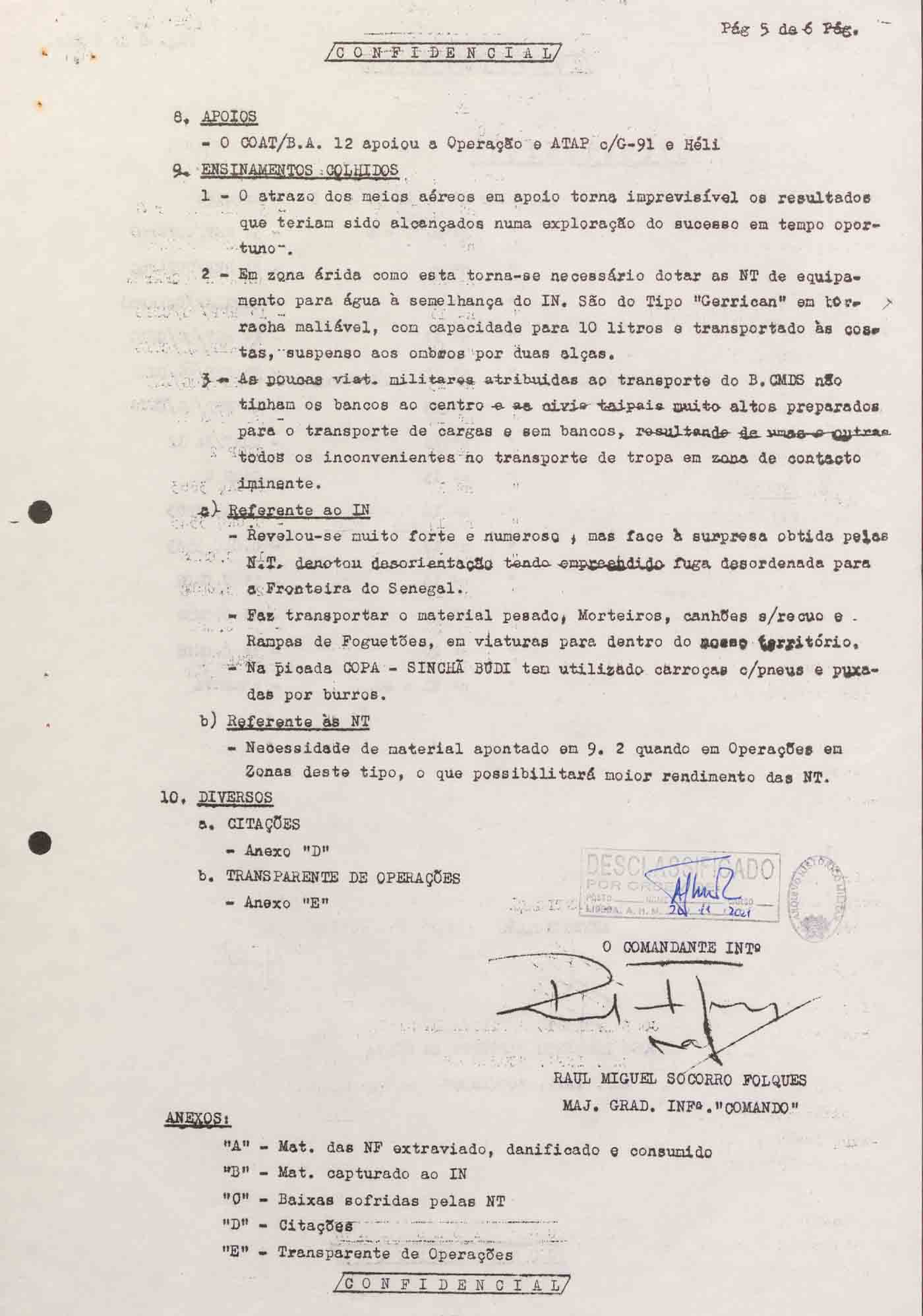

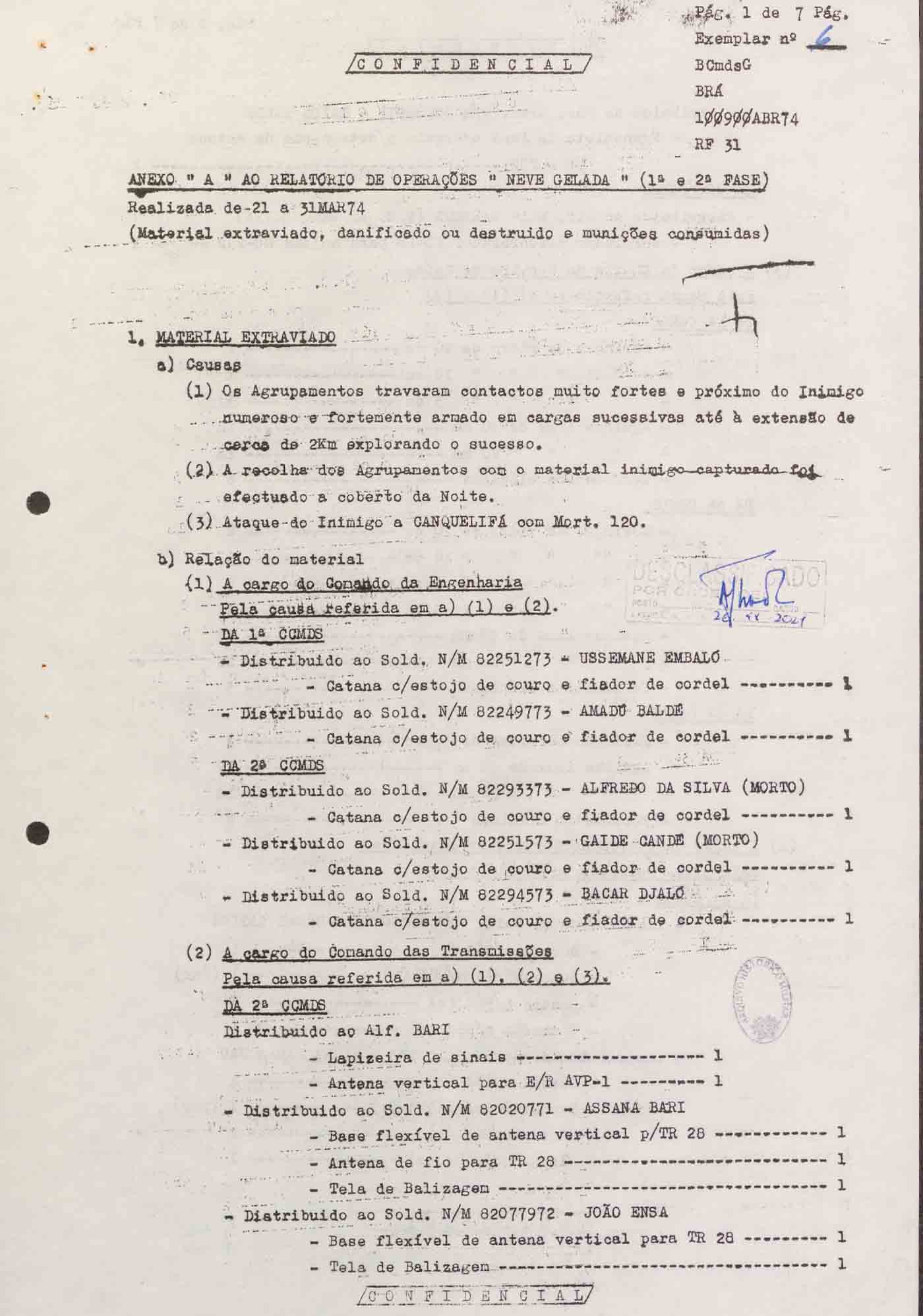

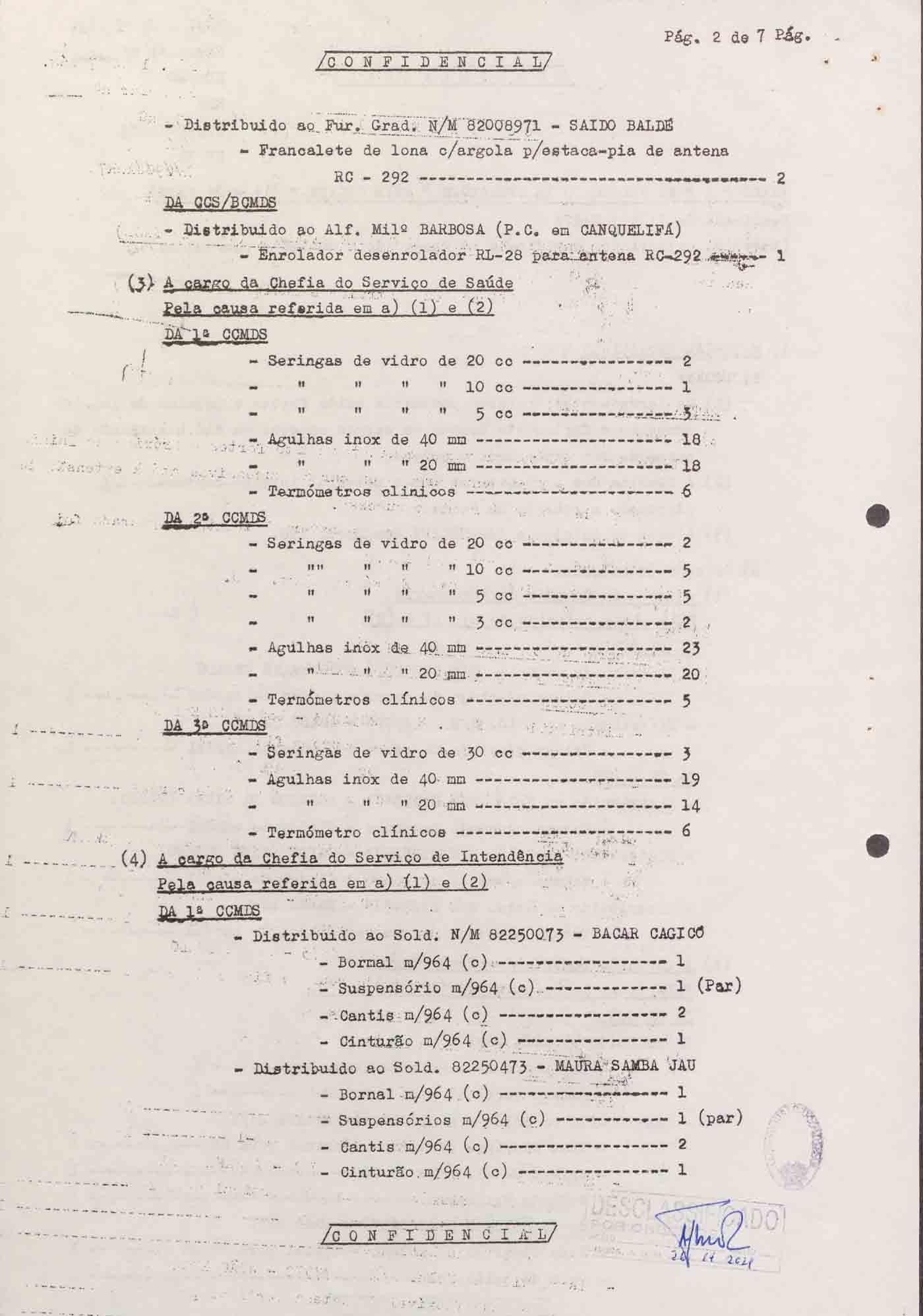

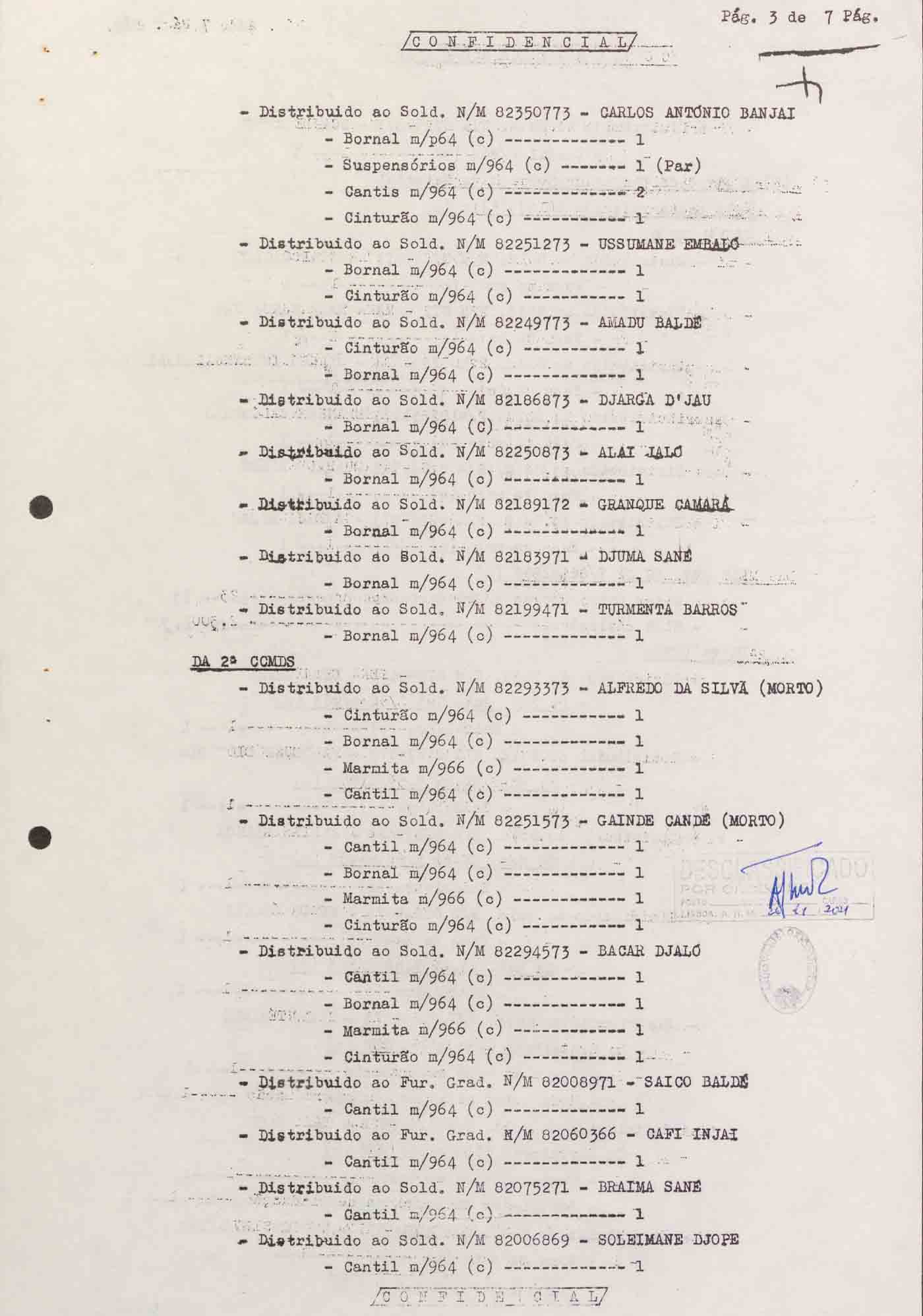

Operações em que os Comandos Africanos da Guiné participaram

Operations in which the Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos participated

Operação:

Operation:

Águia Errante

12 to 16 September

1972

Operação:

Operation:

Bela Madona

7 to 9 October

1972

Operação:

Operation:

Safira Encarnada

8 to 11 November

1972

Operação:

Operation:

Rubi Maior

22 to 27 December

1972

Operação:

Operation:

Falcão Dourado

14 to 17 January

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Topázio Cantante

24 to 27 January

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Esmeralda Negra

13 to 17 February

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Kanguru Indisposto

20 to 23 March

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Ágata Encantada

2 to 5 April

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Jade Errante

20 to 25 April

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Malaquite Utópica

22 to 24 July

1973

Operação:

Operation:

Gema Opalina

24 to 27 September

1973

Every day, at sunset, Abdulai Djaló’s mother sat down and cried. Night after night, even when she closed her eyes, she couldn’t switch off. Alfa, her eldest son, was a PAIGC commander; Abdulai, the youngest, an African commando in the Portuguese army. The thought that two men who had grown inside her could kill one another drove her crazy. Abdulai Djaló, soldier for the African Commandos, 1st Company, is the one telling this story: “Every time I came back from an operation she asked me, ‘Did you see your brother? Is your brother alive?’, I would say he was. There were people in the PAIGC who we would contact to find out about our relatives.”

The men who completed the Commandos training saw their bodies and souls fused into one common objective: to go to the bush, fight the PAIGC guerrillas and get out alive. But none of this was stronger than the link that tied them to their families, nor was it capable of freeing them from the fear that, even today, many don’t admit having felt. “The first time I saw a dead person in the bush, I was traumatized for nearly a week. I’d lie in bed, incapable of sleep. Once I was injured in battle. They took me to the military hospital and I saw troops with no legs, no arms, no eyes. I put my head in my hands and thought, ‘Djaló, this is no life, you could also end up like that’.”

We are a digital publication, but our team works in analogue. We write for people, not algorithms. If you want to suggest a topic, or ask us about our work, send us an email at: info@divergente.pt

Owner: Bagabaga Studios, CRL VAT: 510672531 ERC number: 126622 Periodicidade: anual Director: Diogo Cardoso Editor-in-chief: Sofia da Palma Rodrigues Adress: Rua de Arroios, 25 C, 1150 – 053 Lisboa Portugal

Follow us on social media to find out about our events and follow what is happening at the DIVERGENTE newsroom. We post news there.

“The Portuguese

pitted blacks to fight

against blacks and

then turned us in”

In remembering a youth spent at war, these men feel a mix of hurt and nostalgia. Can the best time of our lives also, simultaneously, be the worst? “I miss it, I was young, strong, we had a lot of fun. In the army, there was no difference between blacks and whites, we were all friends, we all really got on. The worst came after 25 April,” Abdulai recalls.

In the days after the “Carnation Revolution” that overthrew the dictatorship in Portugal, there was a massive party throughout Portuguese Guinea. They predicted the end of the war and the “work”—the name they used to refer to military service. There were a dozen reasons to celebrate. Joaquim Boquindi Mané, who we spoke to in the first chapter, was happy, very happy, when he heard what had happened on the radio: “We knew that Spínola had led a coup against Marcelo Caetano and we all took to the streets to celebrate.” They talked, hugged and shouted for the world to hear, “The war is over! The war is over!”. They even sang fado: “The troops from Portugal sang pretty tunes, they said, ‘I’m going home’, ‘Guinea, I’m leaving, I will miss you, but I’m going to see my mother and father…’”

Everyone was still exuding joy when the PAIGC commanders started to arrive in Bissau and explain to the Africans in the Portuguese Army that the whites were leaving. That, from thereon in, all the children of Guinea-Bissau could get along. Galé Jaló suddenly got a bad feeling and decided to go back to Quebo, where he had lived before he was recruited: “I left the uniform, and everything that could be used to identify me, in the place I lived in Bissau. I left the key in the door and came straight back here as a civilian and started to work the fields. If I stayed, I knew I’d have problems.”

Fernando Cabral

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“25 April? I remember it. Are you happy when you go to war? Tell me! Are you happy with war? If I said that I wasn’t happy when the war ended, I’d be lying. Independence was a good thing for Guinea-Bissau, how could it not be?”

Luís Sambú

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“I think that it was a bad thing to make Africans fight Africans. It was unfair. The Portuguese pitted blacks to fight against blacks and, when the situation got difficult, they turned us in. When the war ended and the PAIGC machine came in, there was nothing we could do.”

Lamine Camará

Soldier

Portuguese Guinean section of the African Commandos, 1st Company

“If we’d known that the PAIGC were going to win the war, no one would have joined the army. Because the ones who fought with them [PAIGC] were black like us, they wanted independence for us. If we’d all got together, we’d have been stronger. But, as we didn’t know, the Portuguese lured us away.”

The African Commandos were the front line for the Portuguese Army in the struggle against the PAIGC. They were the last hope for the governor António de Spínola to make his vision of a State where he imagined the Portugal of the future a reality—a European and African country in which whites and blacks would have the same rights and duties. What he seemed to fail to recognize was the unequal power relations that had, for centuries, created a gulf of inequality between the European and African peoples.

Source:

“Portugal e o Futuro”, António de Spínola

When the 25 April military coup was announced, the African troops still feared nothing: they foresaw the end of the war and, with that, a less fragile and uncertain life. After all, it was Spínola, the man who had promised them everything, who had proclaimed the formation of the National Salvation Board on the radio and guaranteed the “survival of the nation as a sovereign homeland in its pluricontinental entirety”. It was only months later that the African Commandos had a feeling that they were on the losing side, and would suffer the consequences. When they began to be persecuted, when the beatings and summary executions started.

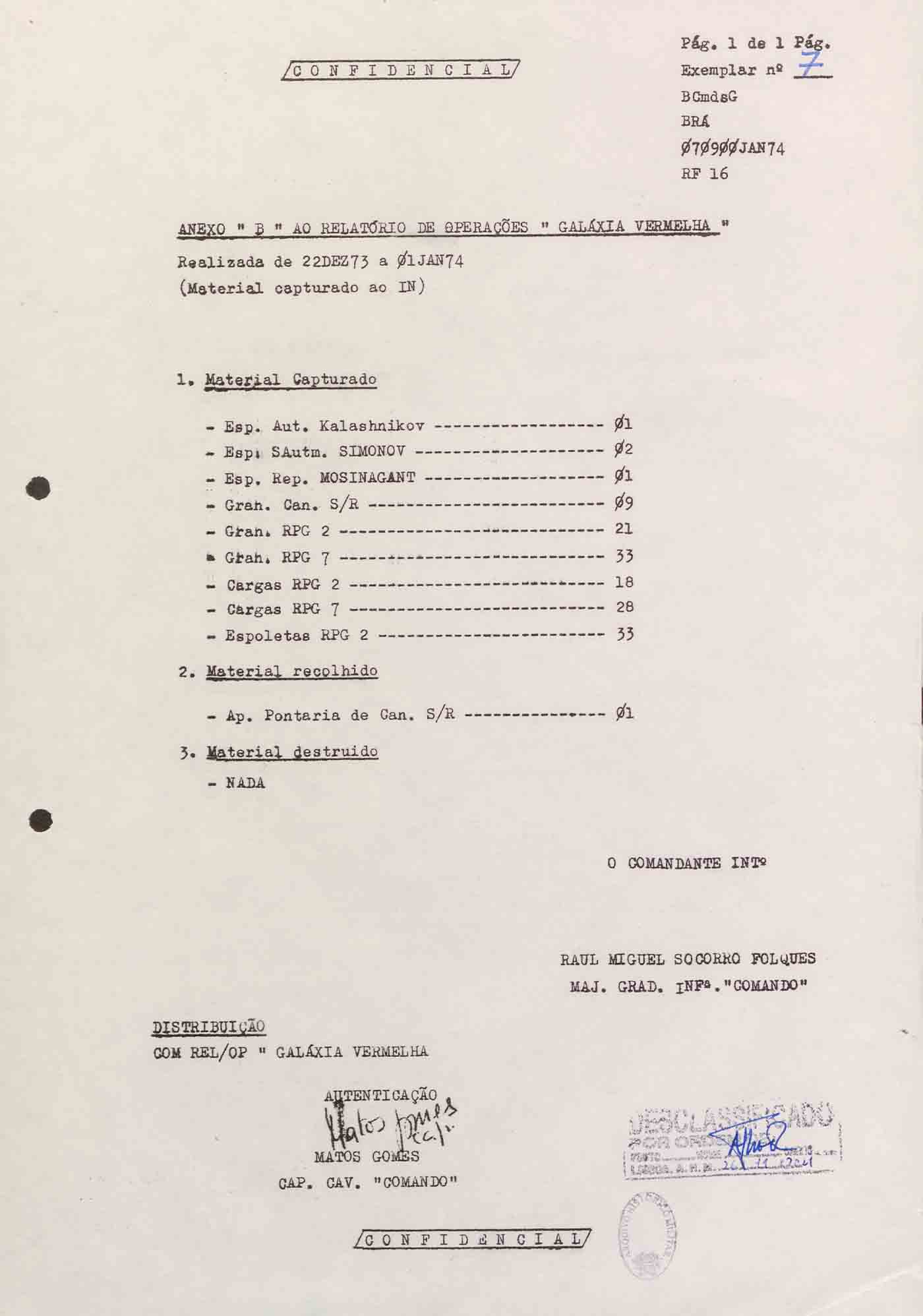

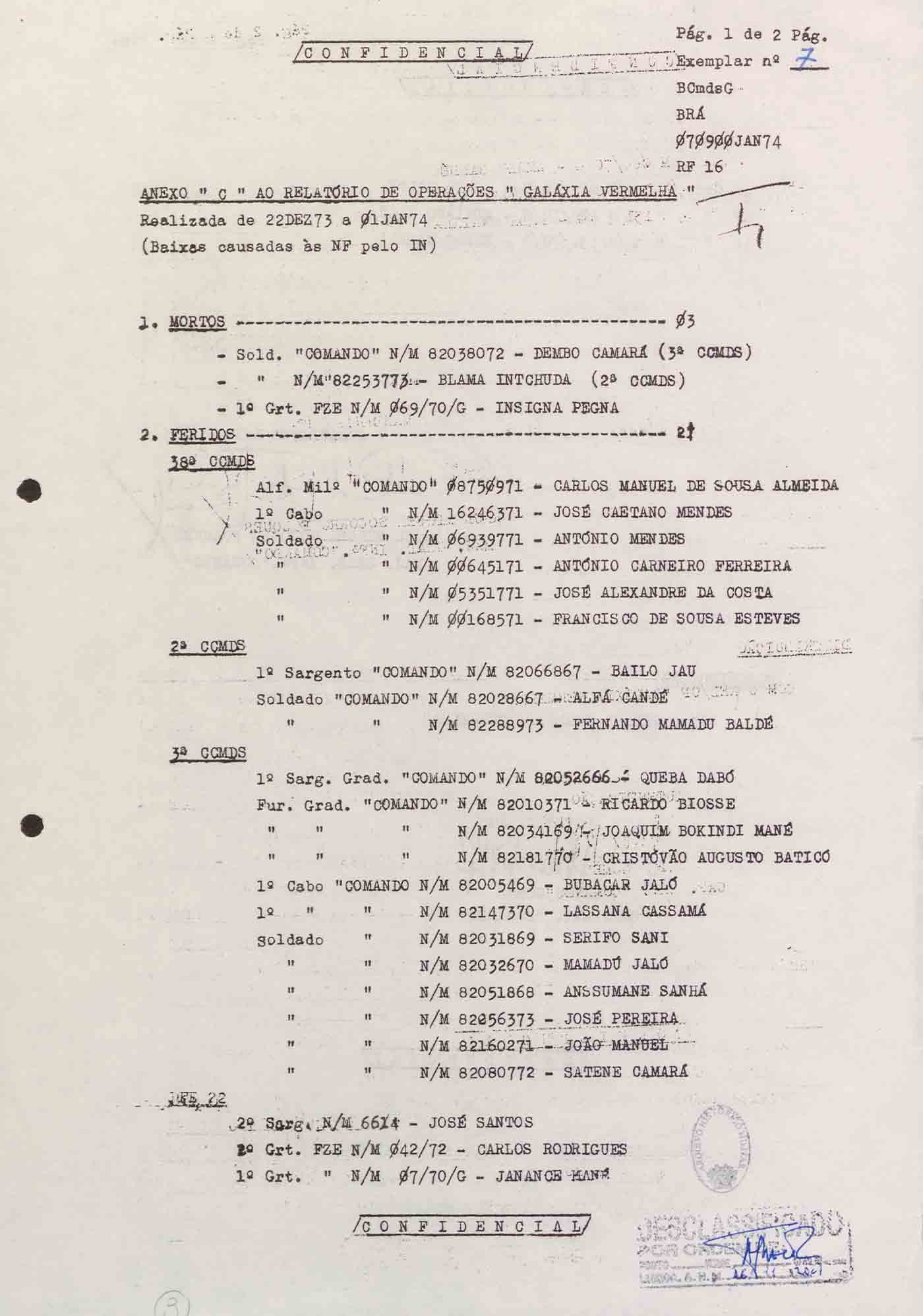

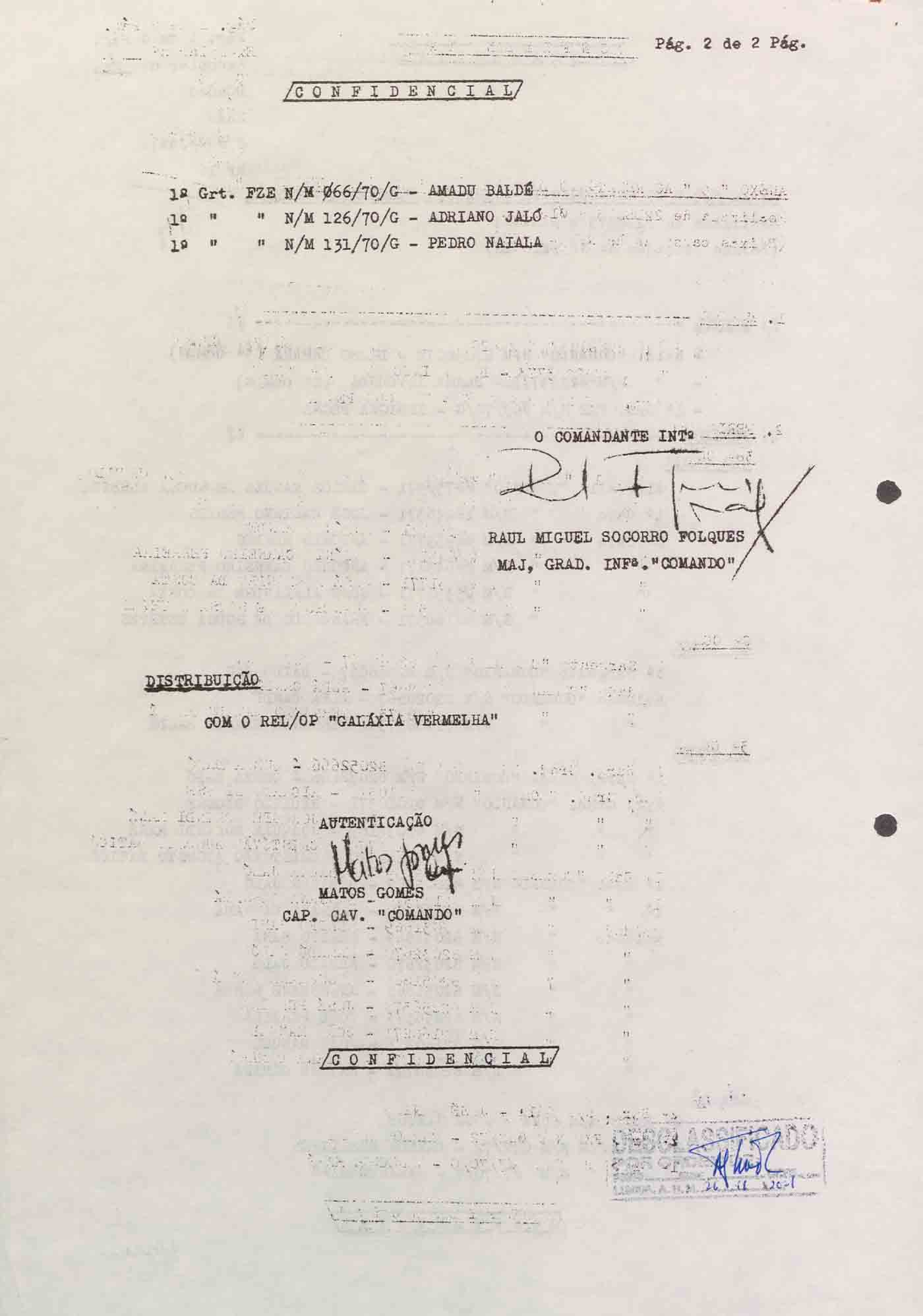

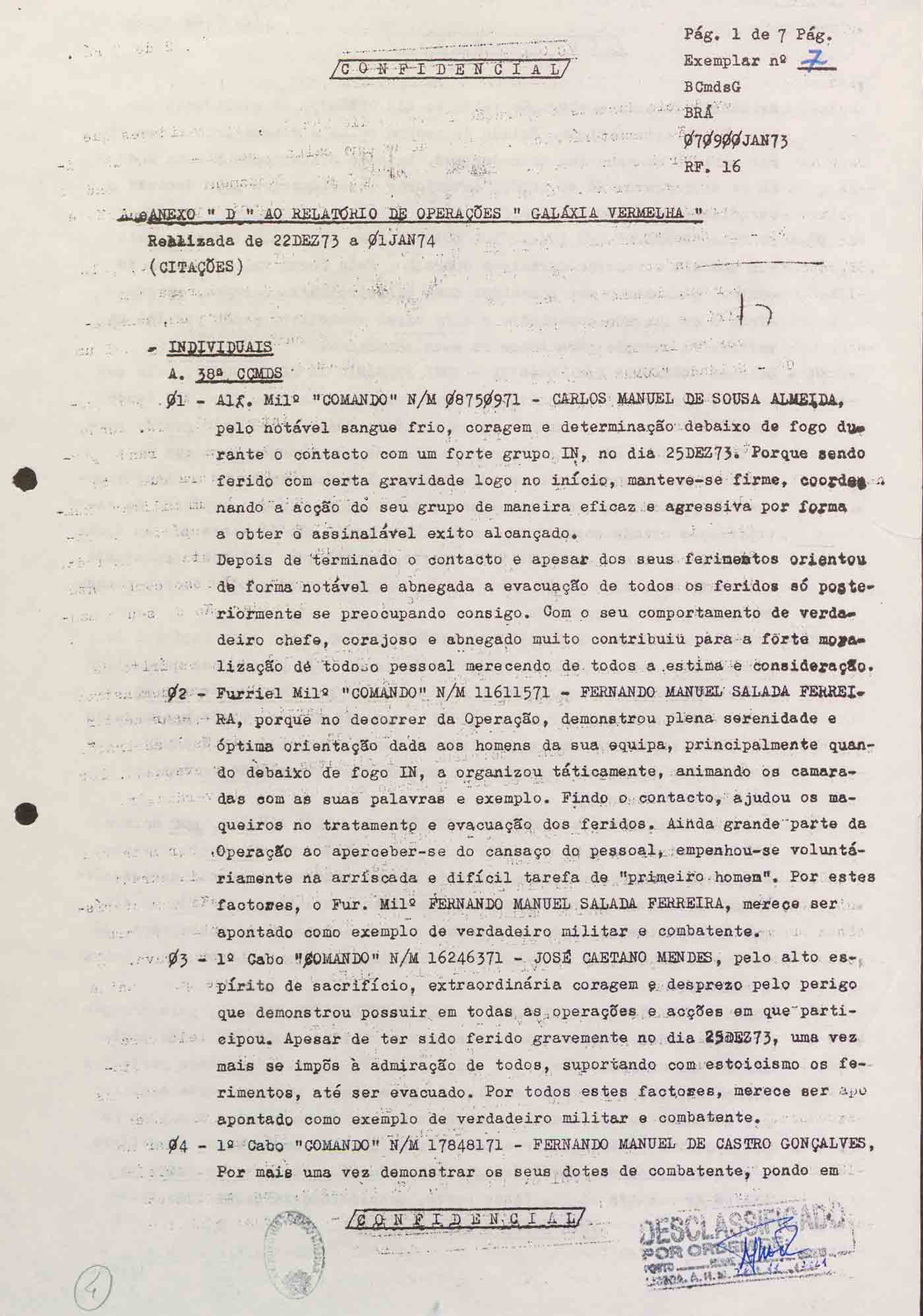

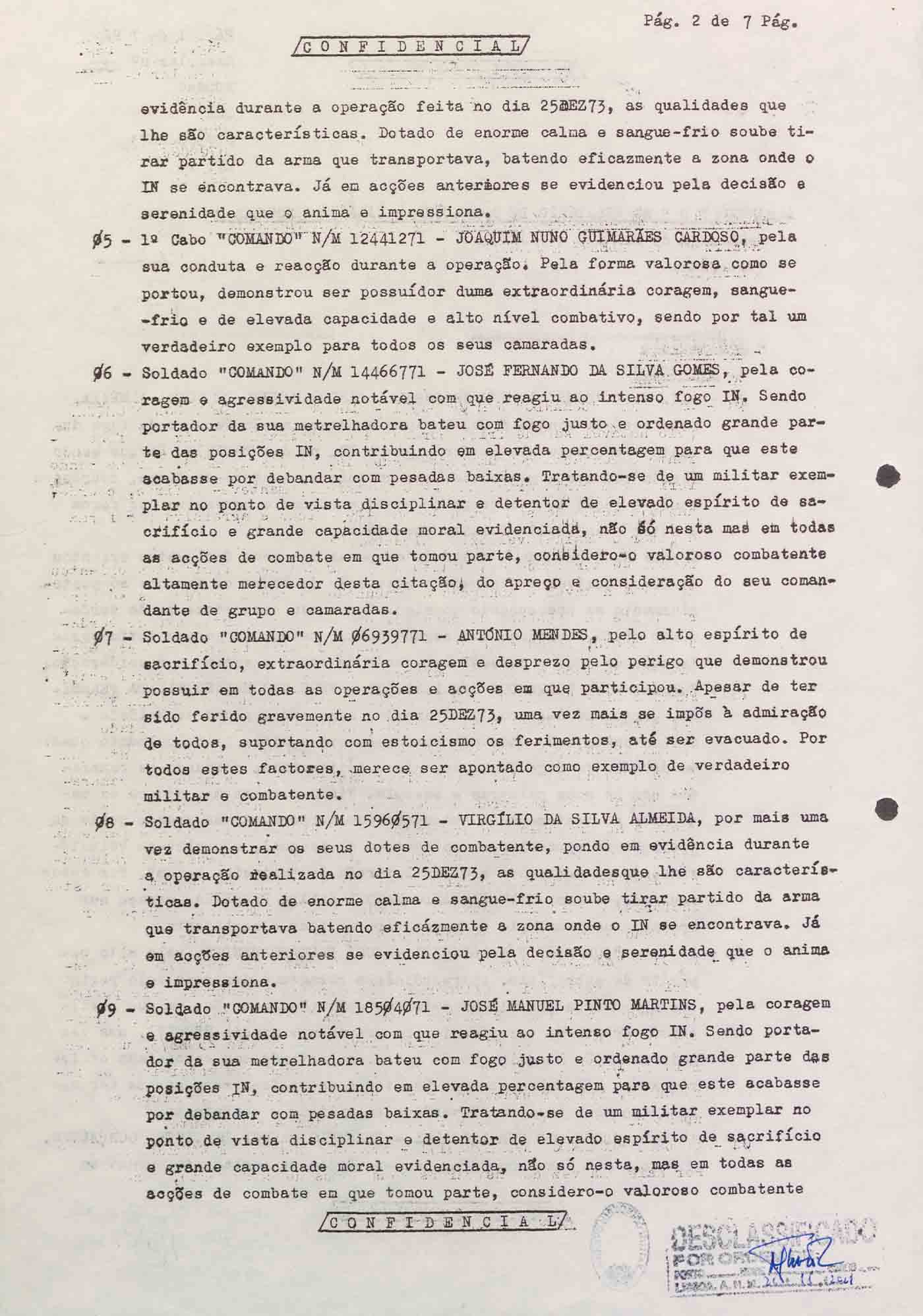

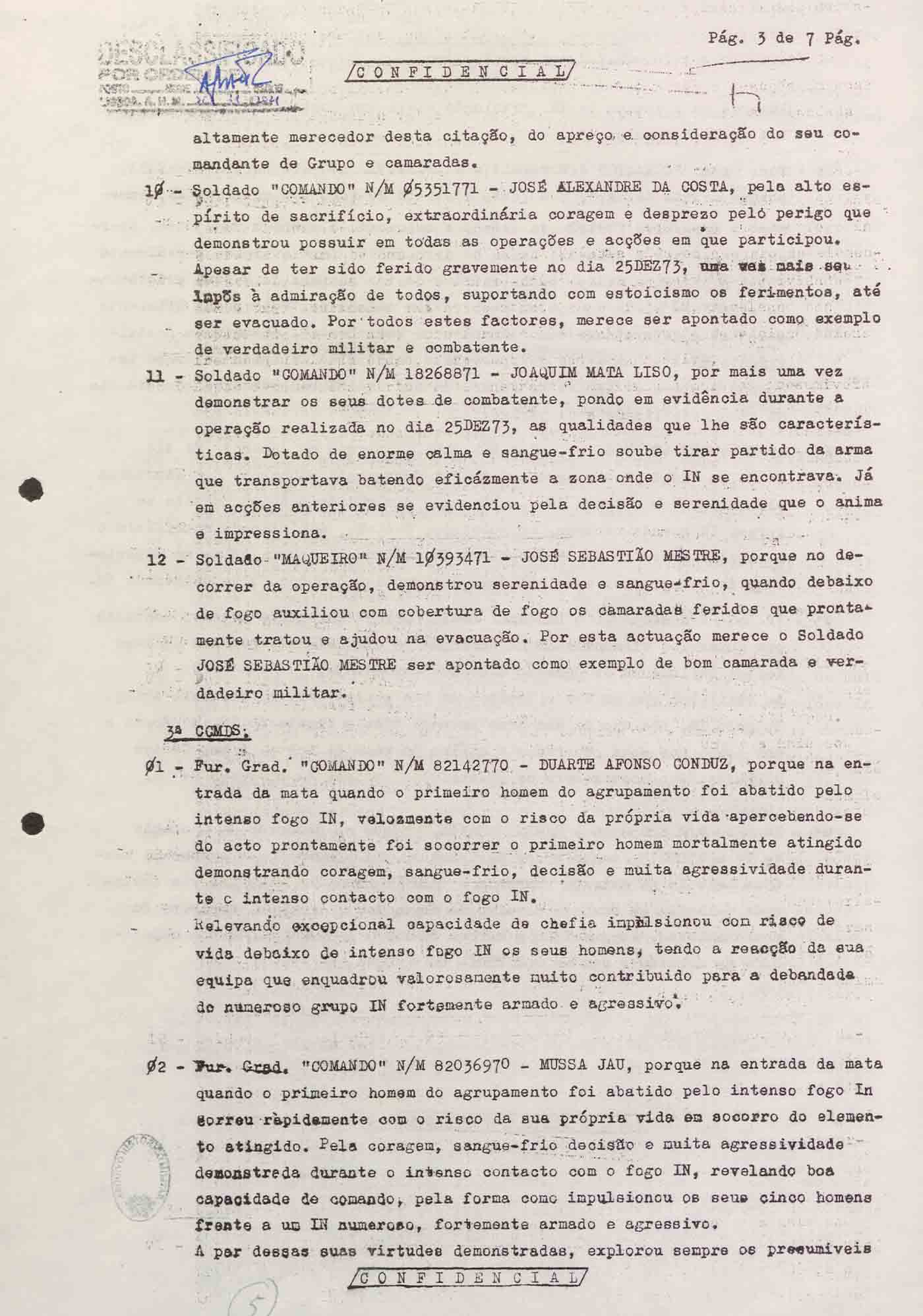

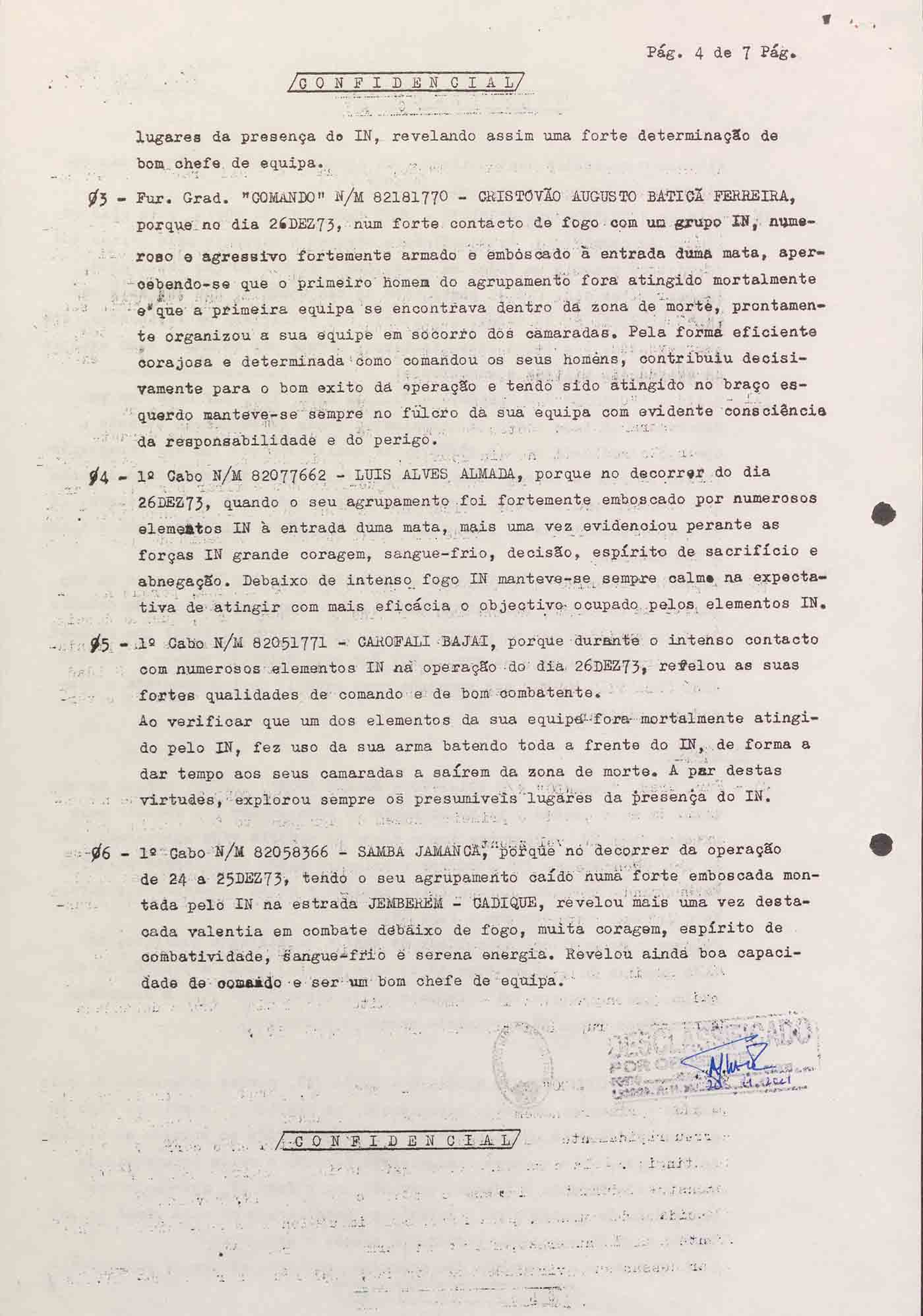

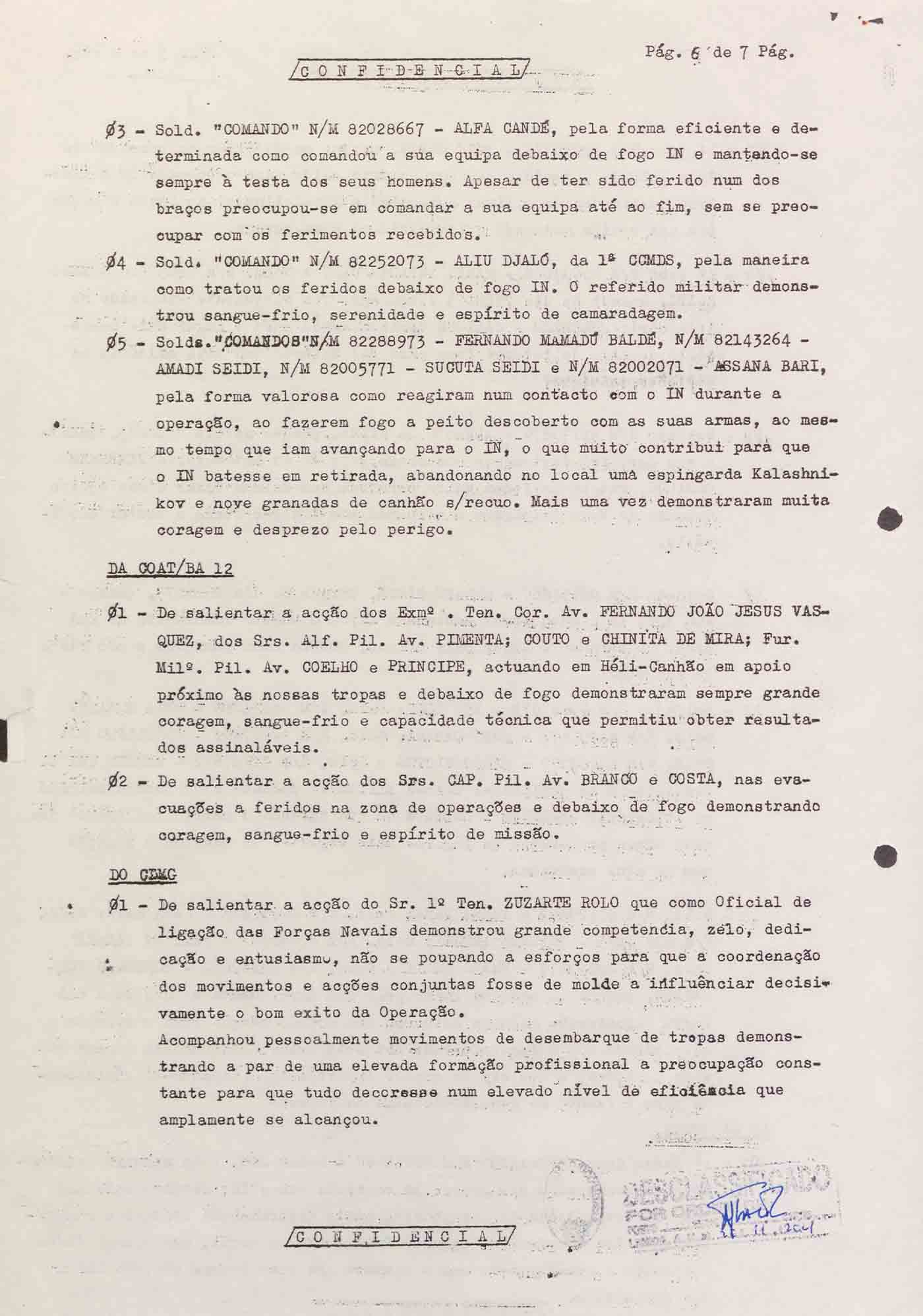

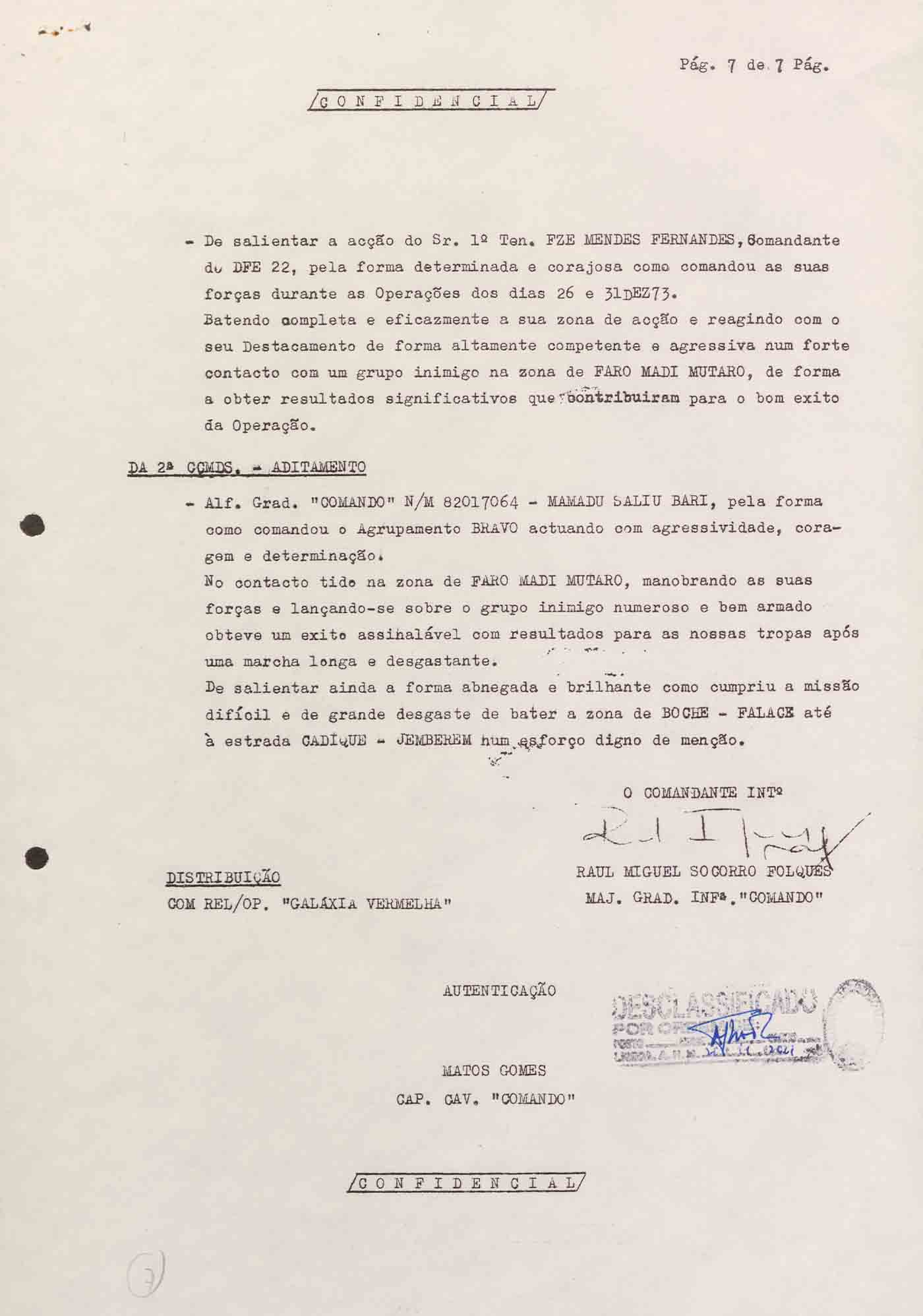

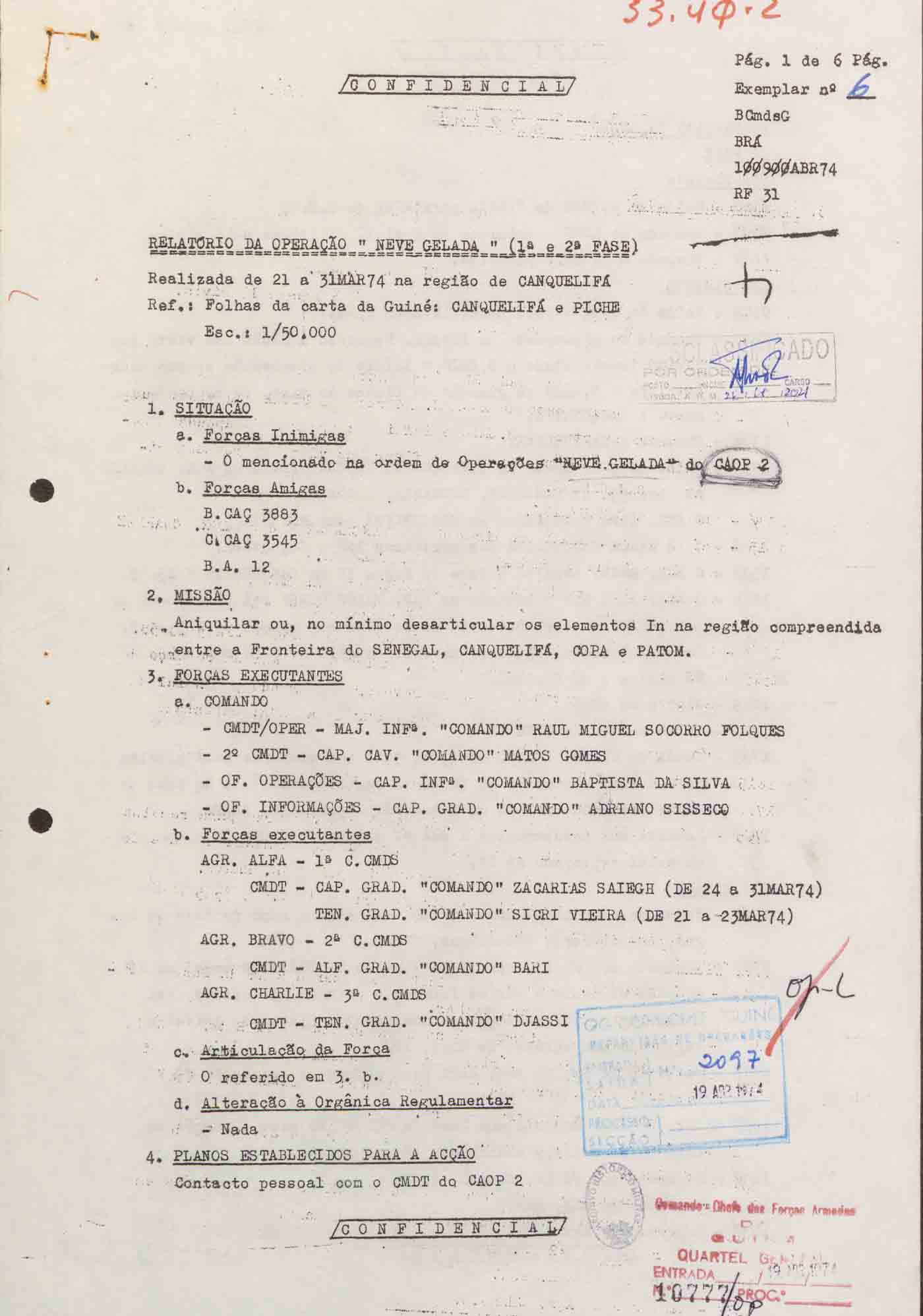

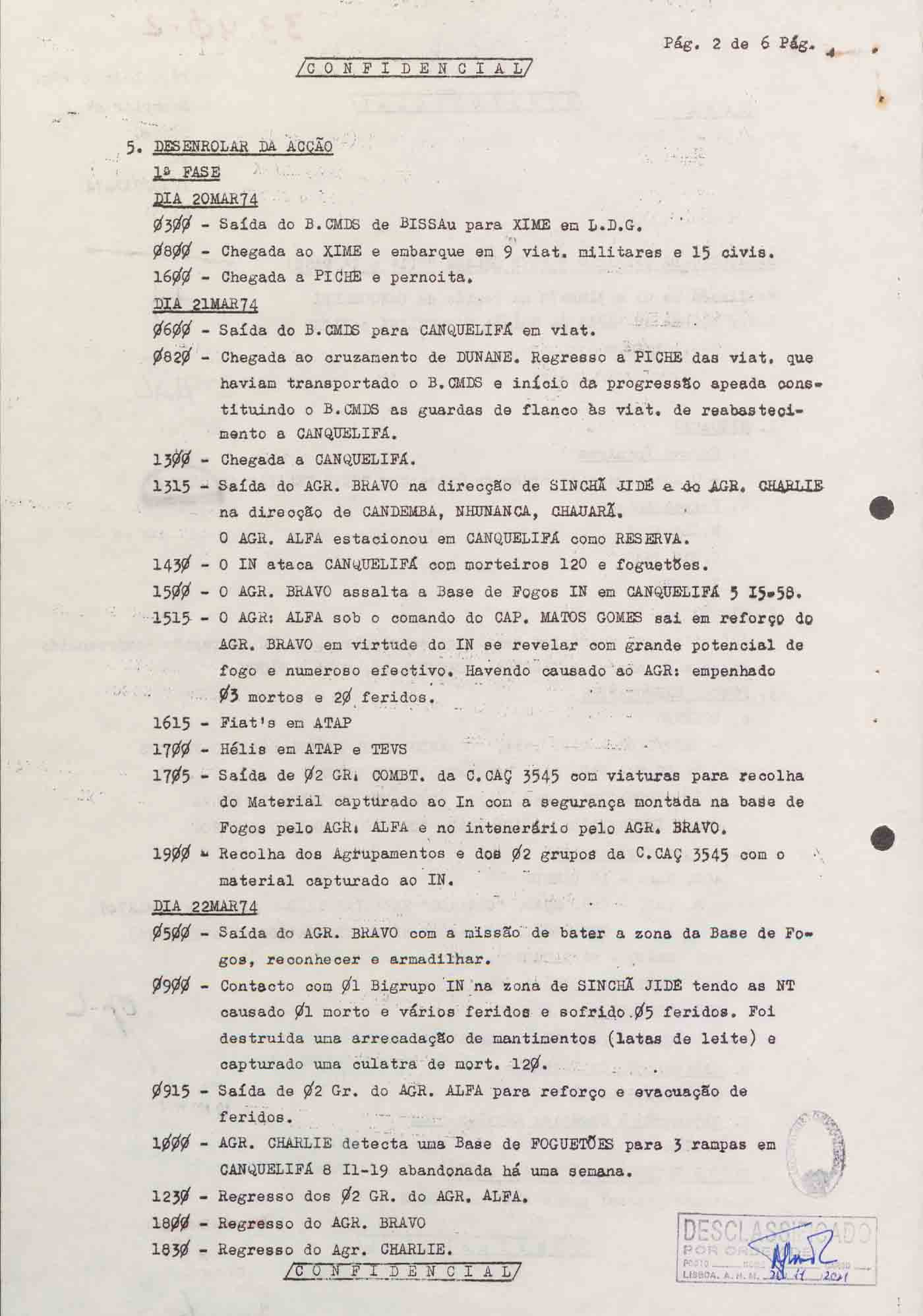

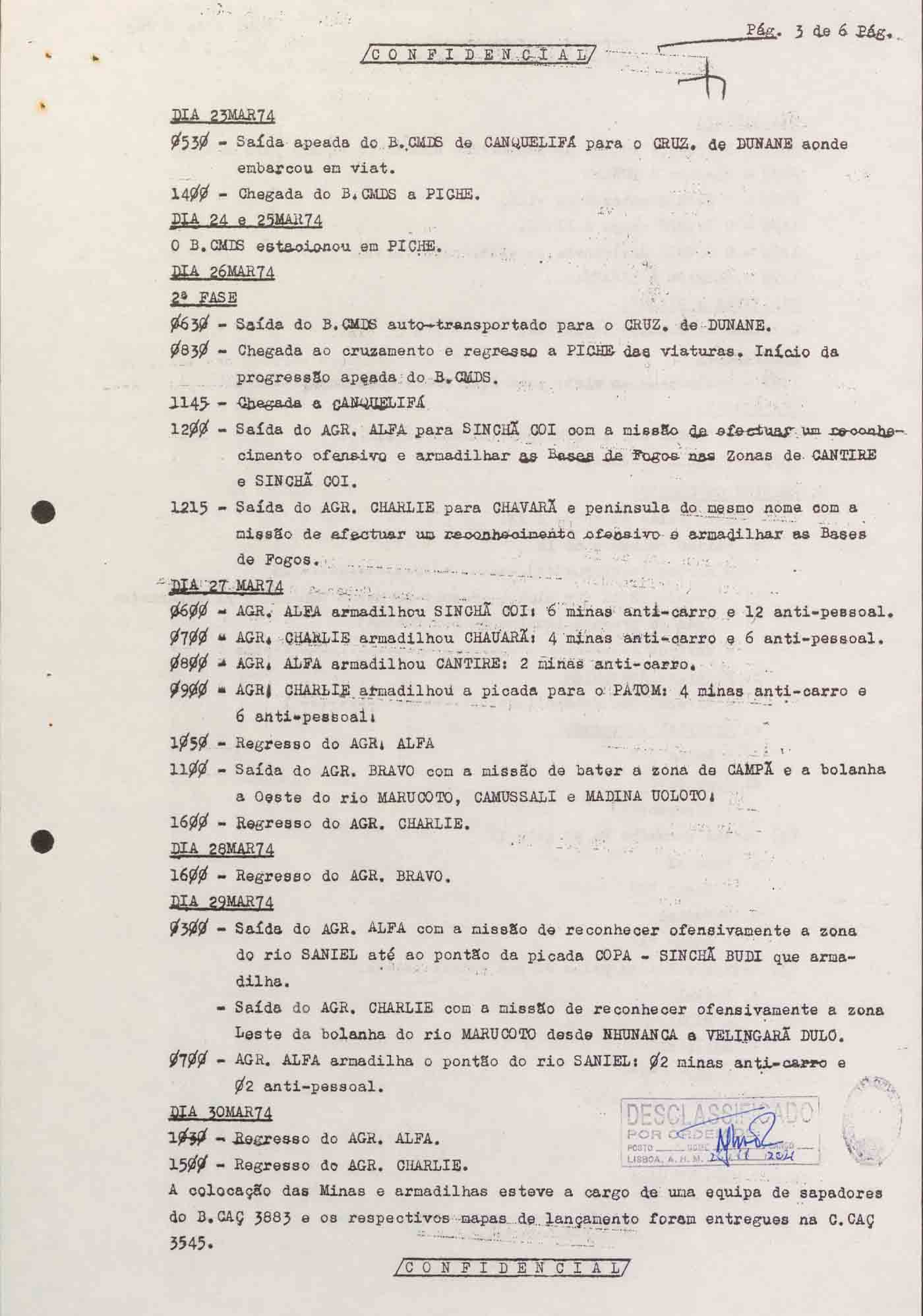

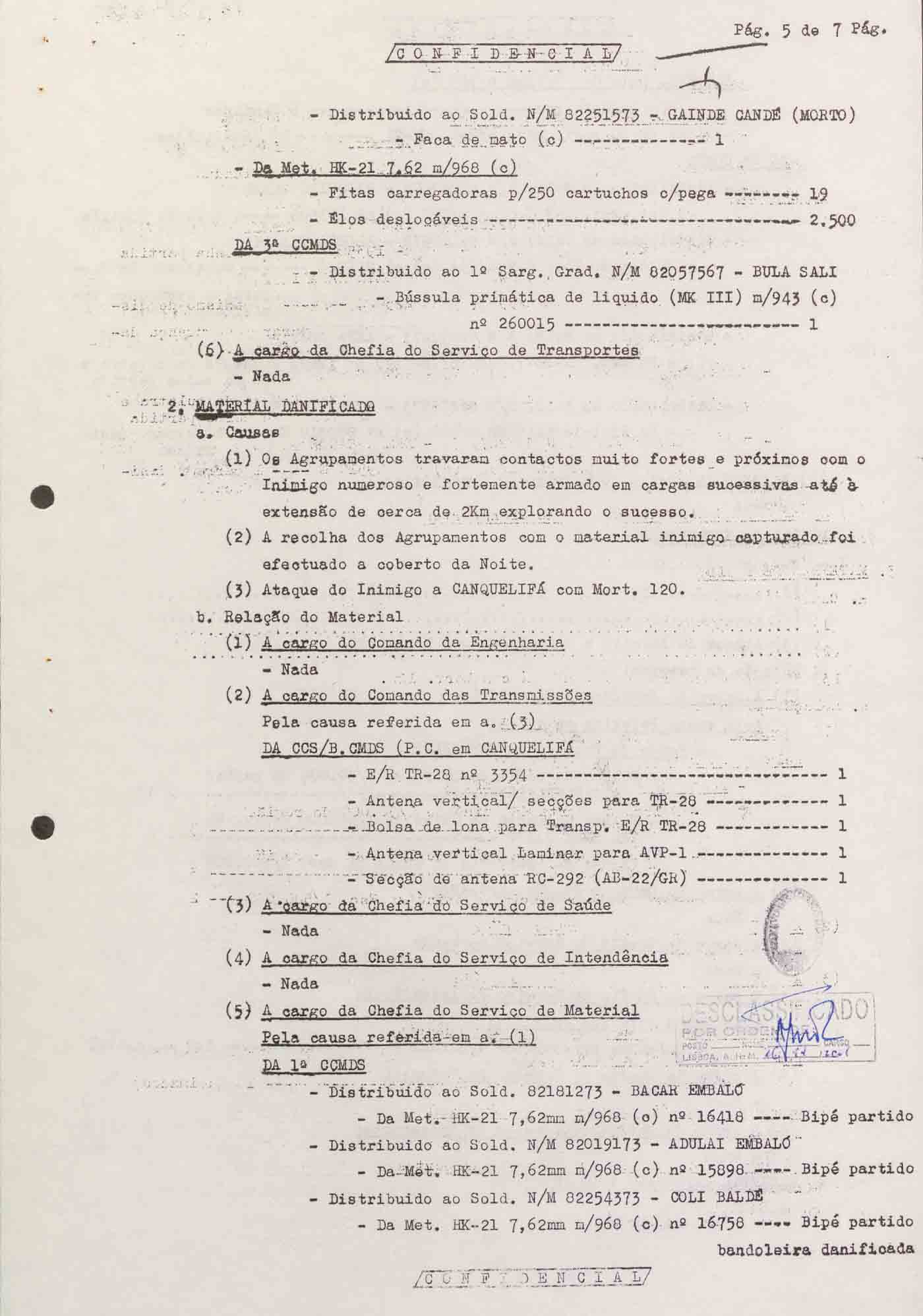

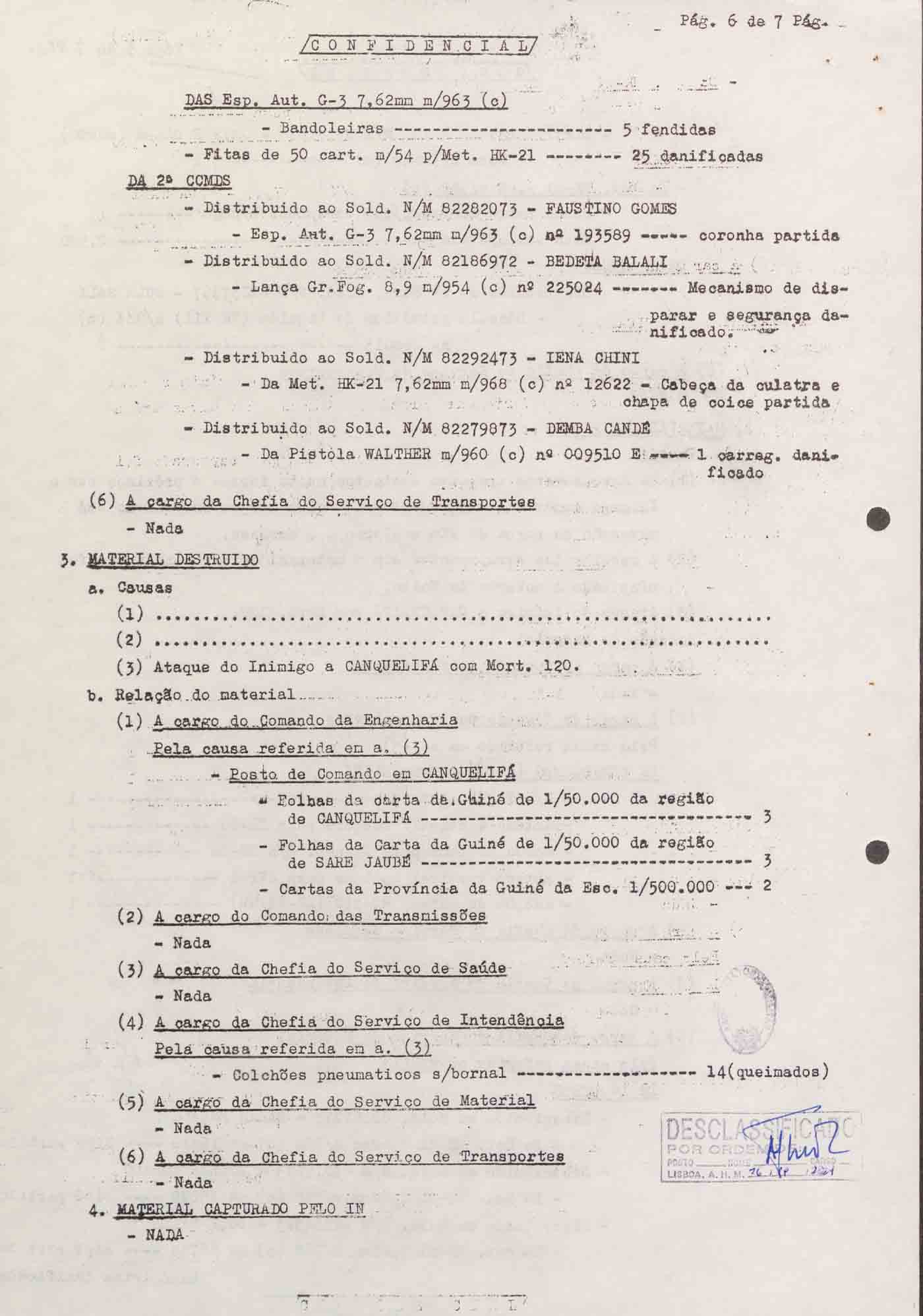

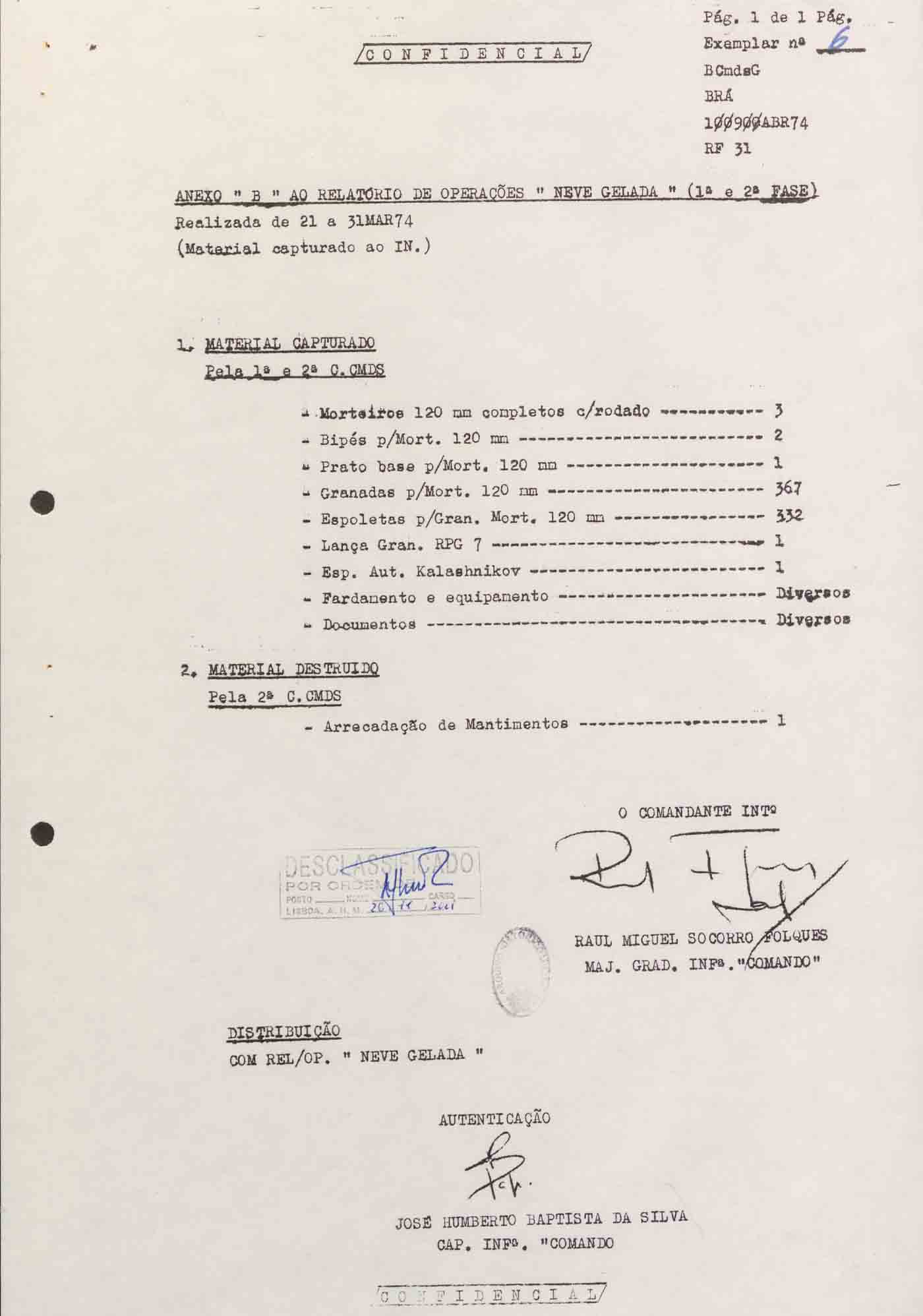

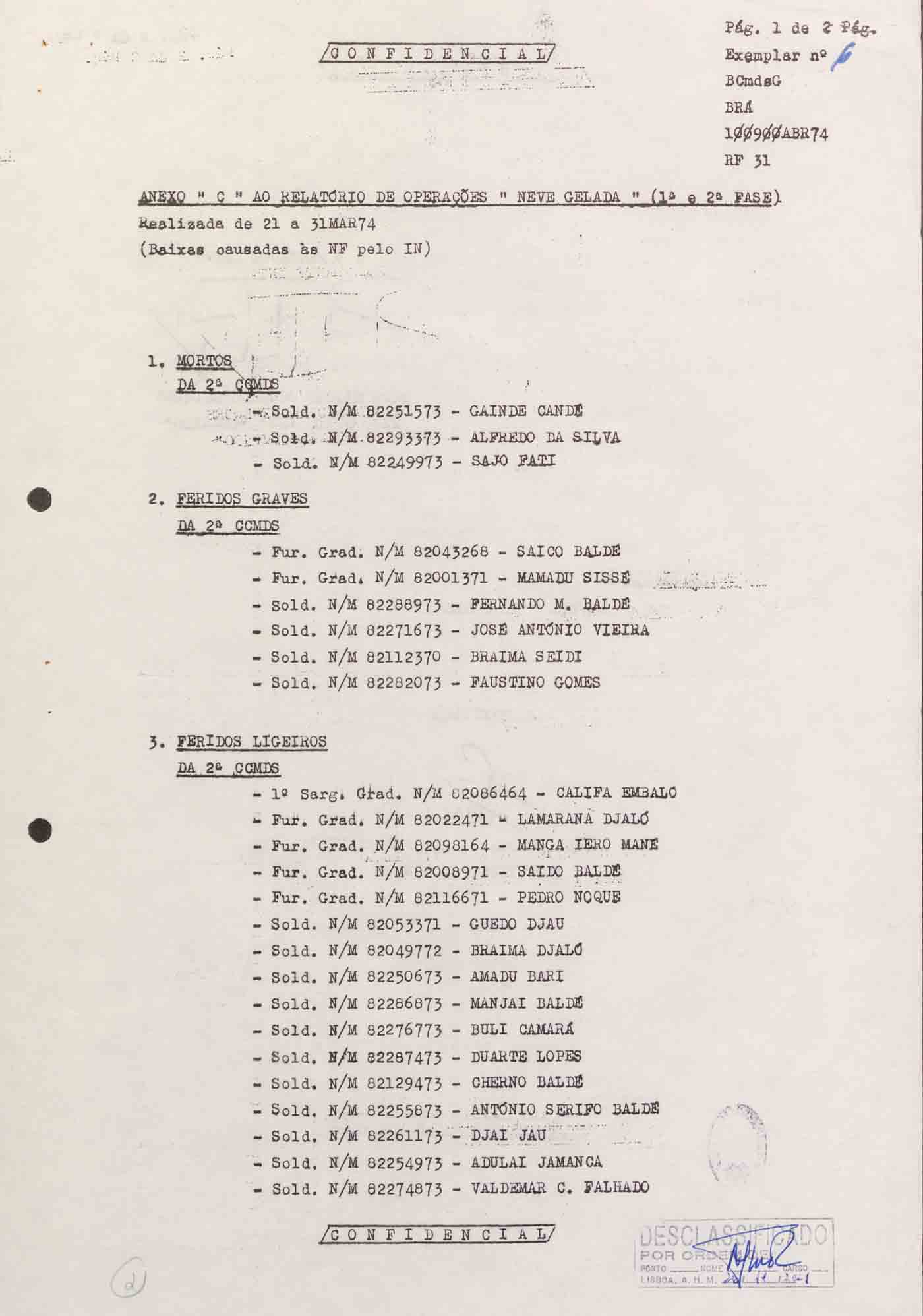

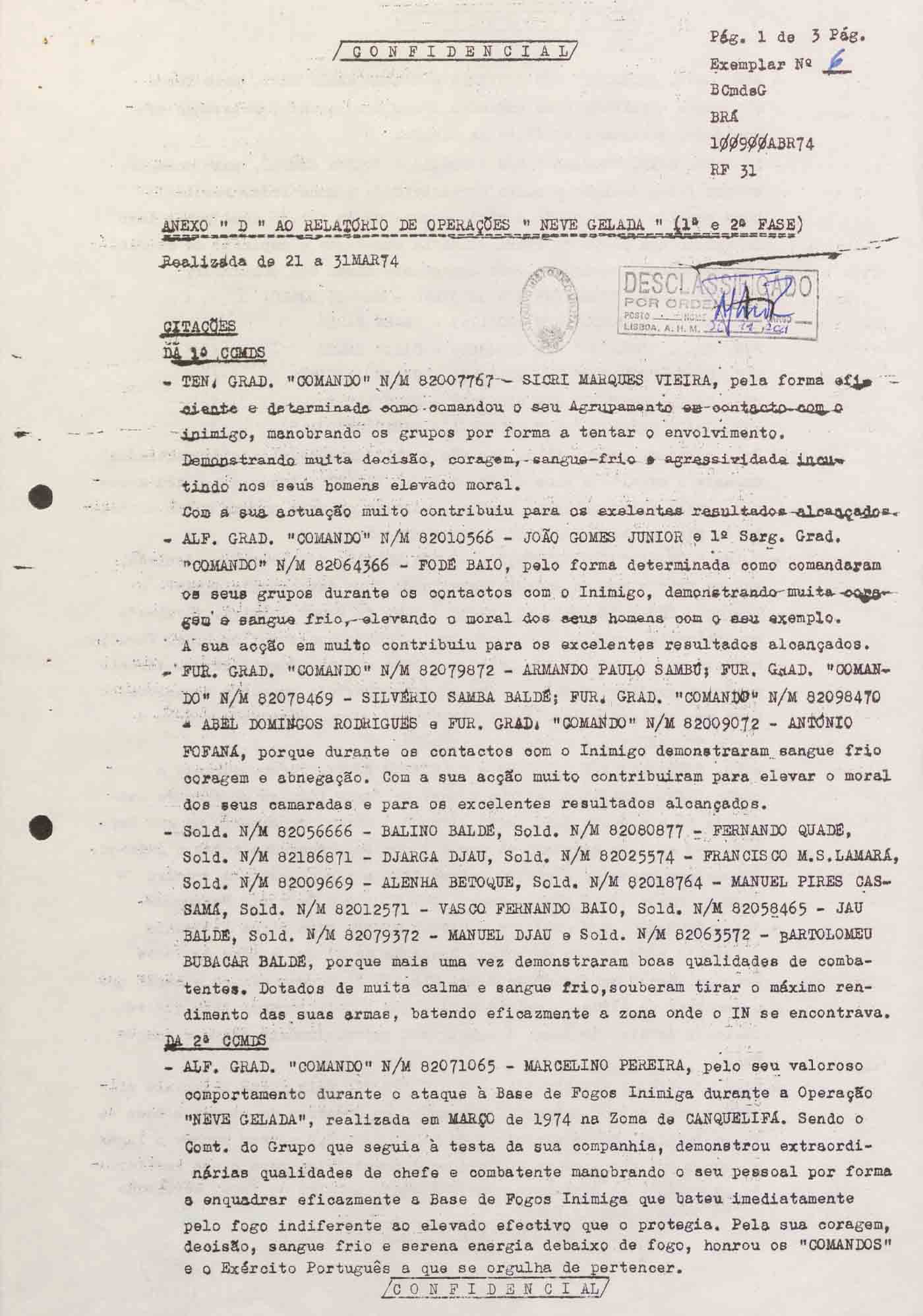

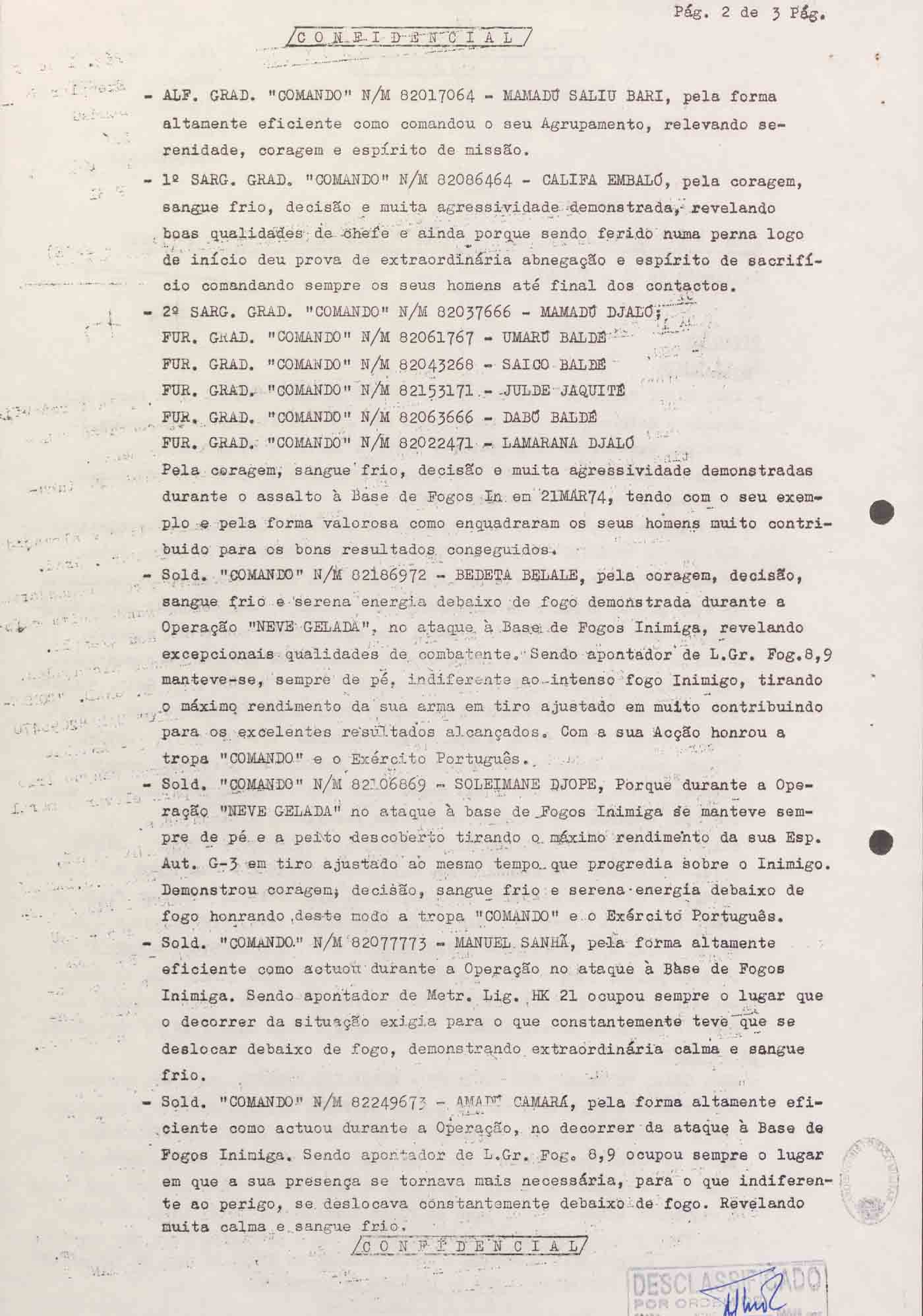

Por graficamente não ser possível a identificação individual de cada uma das imagens, enumeramos aqui a sua origem e cota.

As it is not possible to individually identify each of the images within the body of the work, we specify here , in order of appearance, the origin of each image and its reference number.

We are a digital publication, but our team works in analogue. We write for people, not algorithms. If you want to suggest a topic, or ask us about our work, send us an email at: info@divergente.pt

Owner: Bagabaga Studios, CRL VAT: 510672531 ERC number: 126622 Periodicidade: anual Director: Diogo Cardoso Editor-in-chief: Sofia da Palma Rodrigues Adress: Rua de Arroios, 25 C, 1150 – 053 Lisboa Portugal

Follow us on social media to find out about our events and follow what is happening at the DIVERGENTE newsroom. We post news there.